There are a small number of things to be grateful for in this report on English teaching by Ofsted:

- A clear and repeated recognition of the damaging effects of ‘excessive practice of a narrow range of writing structures to prepare students for GCSE’; this is accompanied by a recognition that students need more opportunities to draft and edit work and to write in forms other than those used in tests and exams.

- A recognition that over-reliance on writing structures and scaffolds is having a negative effect.

- A valuing of ‘oral composition’ in its own right, not necessarily always requiring a written product at the end.

- The flagging up of non-fiction as an aspect of the English curriculum that needs more attention.

- A recognition that CPD that goes beyond assessment and examining is important.

- An acknowledgement that students need exposure to lots of texts across the English curriculum.

- A stress on the importance of developing a reading culture in schools.

- An understanding that students need plenty of material to work with before they begin writing.

However, there is also a great deal to be concerned about in this report. We think it worth taking the time to discuss these concerns in detail, even though it is quite a long read.

1. The report is predicated on, and entirely framed by the English Research Review that was so heavily critiqued in many quarters. As a result, its findings are filtered through the lens of a body of research that is of questionable value in relation to the subject. It excludes a huge amount of knowledge and understanding about the nature of the subject – based on much more sophisticated and grounded work around almost everything that this report is concerned with, such as reading, comprehension, the writing process, the nature of spoken language, grammar, the way literary study works as a subject discipline and so on. This emerges at every level of the report, in ‘gaps’ and ‘misconceptions’ about key aspects of the subject (to coin terms that are frequently used in this report.)

2. The whole conception of ‘foundational knowledge’ and ‘the basics’ in relation to both reading and writing is based on highly dubious thinking about the nature of English as a discipline and how students learn all the various elements within it. First this, then this, then this has been shown to be an inappropriate way of thinking about both reading (and reading comprehension) and the development of writers from early years up to the end of compulsory schooling. Comprehension of written text starts way before decoding is under way. Writers can compose before they have ‘mastered’ spelling and grammar. The idea that they need to ‘know’ grammar before they can write shows complete lack of understanding or awareness of the most significant research into grammar and writing done by Myhill et al at Exeter University.

3. On writing, there is a thin, muddled, un-evidenced entirely linear view of how writing develops, without any understanding of the complex interplay between writers’ intentions, composition and technical skills. It’s all presented as a simple sequence that can be ‘explicitly’ taught. It is presented as ‘components’ that are put together, and have to be taught before students can make meaning. This is patently untrue. The wonderment expressed by the report writers at children continuing to make errors in their own writing, as if they either haven’t been taught the ‘rules’ or haven’t been ‘corrected’ enough is an indication of how little the writers of this report understand about the complexities of the process of teaching writing and learning how to write. Criticising teachers for not teaching spelling or punctuation, or not always correcting every error is not fair, and is based on erroneous ideas about how children’s writing develops. It’s worth thinking about the idea of breaking down the teaching of writing into its component parts as an example of the report’s basic misconceptions. Writing can be seen as involving over 50 component parts and it’s impossible to separate these out and write without drawing on several at the same time. It’s also unreasonable to think that these can be sequenced in a meaningful way, one at a time. By all means, encourage teachers sometimes to focus on a single element of writing, but ways of teaching writing that recognise that this oversimplifies the whole process are important and need to be part of any English teacher’s repertoire.

The talk of there not being enough explicit teaching of ‘simple direct standard English’ is another example of the confused thinking. What is this? Learning how to make meaning is absent from the discussion of writing. Instead it is broken down into a series of functional right/wrong processes that are of limited value to learners when removed from a purposeful context.

4. The discussion of spoken language is one of the most depressing parts of the document, showing a poor understanding both of how spoken language works, and differs from writing, and also a very sketchy understanding of what English teaching of spoken language should look like. There is no clear distinction made between teaching students how to talk (the performance of talk) and talk for learning – seemingly with no awareness that the latter might not involve teaching students ‘forms’ and ‘vocabulary’ and rehearsal and re-framing of students’ speech. Talk seems to equate to presentations and to being taught to do these better. The idea of practising written sentence structures orally with a view to improving writing shows fundamental misunderstandings about how spoken language differs from writing.

Comments like ‘Some pupils do not develop the confidence that comes from having the knowledge they need to speak clearly and express their ideas’ risk misunderstanding where confidence in speech comes from and failing to recognise the rich linguistic repertoires that children bring with them into classrooms. Confidence in speech comes from a relaxed enough environment for students to ‘float their own notions’ (Bullock, 1975) without fear of constant correction.

5. On reading, there is much to be concerned about. The teaching of reading in primary is for others to comment on, though we’d note the problems in the dominance of phonics in the early teaching of reading and the failure to recognise the close connections between decoding and comprehension. At secondary level, the failure to focus more attention on comprehension is a significant feature in low attainment in reading.

At secondary level, we would seriously question some of the assertions about ‘challenging texts’ and what that actually means, along with the term ‘literary merit’. This is never defined but seems to mean texts with more challenging vocabulary and syntax and seems, in the view of the report writers, not to be associated with texts that raise issues of social justice or speak to students’ own experiences. This leads to a very narrow idea of challenge, and of what literature is and what it can do for you.

A book like Keith Gray’s The Climbers is easy to decode, does not have challenging vocabulary or syntax but is a very challenging (and engaging) text for all kinds of other reasons. It is the kind of text that can both present challenges, and raise social issues, and appeal strongly to young people because it speaks to their realities. Careless equating of this kind of book with low challenge is very damaging. The writers of the report might like to consider reading as a two-way process, where a student’s development does not come simply from tackling ‘more challenging’ texts, but from learning to read all kinds of texts with increasing degrees of sophistication. Having important things to say about texts that, at surface level, might present as being relatively straightforward, is perhaps just as important as being able to understand more complex material. It’s also key to developing the ‘disciplinary skills’ that the report is keen to stress. It’s very difficult for students to develop these skills when so much cognitive load is engaged simply with trying to understand a text; where understanding is clearer, then real attention can be given to complex skills of analysis and interpretation.

6. The emphasis on vocabulary persists but perhaps with a growing recognition of some of the impact of word lists, vocabulary taught out of context and other decontextualised approaches. In a similar way, there are references to retrieval practice, quizzing and so on but the comment on schools not necessarily having thought hard about how these apply to subject English is perhaps an indication that what they have been seeing in schools is retrieval practice and quizzing that isn’t really very effective in relation to the subject.

7. There is an excessive focus on using written models as a pedagogical tool for developing students’ reading and writing. It is a valuable tool but metastudies into teaching writing (Graham and Perin, 2007), for example, suggest it is less effective than several others. Over-use of this kind of modelling risks giving the illusion of a successful outcome by students. There is a risk that they replicate features of the model without engaging in the self-reflective cognitive processes necessary to become competent, self-directed writers. Sometimes more learning is taking place in messier, less perfect pieces of writing.

8. On several occasions, the report lays the blame for what it regards as poor practice on schools, English departments and teachers, rather than recognising some of the systemic problems that have arisen due to the pressures placed on teachers by high-stakes testing and by external pressures from bodies like Ofsted to teach in ways at odds with how language learning and literature learning take place (e.g. a strong focus on direct instruction; mastery learning; a discourse denigrating group work and carefully guided instruction; notions of ‘novices’ and ‘experts’, and so on). Statements like ‘Few schools design or follow a curriculum to develop pupils’ spoken language’ and ‘schools often encourage excessive practice of a narrow range of writing structures to prepare pupils for GCSEs’ might reflect what was observed on the ground, but the tone is off-putting and fails to explore why these things might be happening. They are both examples of where some indication of the kinds of schools being inspected would be useful.

Which schools did the Ofsted inspectors look at and how they were chosen? Were they MATs? Were any of them schools which followed a standardised curriculum such as ARK Mastery Curriculum? Were they schools known to the Ofsted inspectorate or chosen at random? Were there deliberate attempts to look at schools adopting different models, with different philosophies that achieved well in different ways? This would all have been very helpful to know. Are the practices critiqued in the report more present in some kinds of schools than others, for example? Other studies have shown that the more disadvantaged a school’s intake, the more likely it is to limit the use of spoken language in classrooms while also spending more time than other schools teaching directly to GCSE examinations (Hutchings, 2015). This kind of nuance in the reporting would, in and of itself, shed light on the impact of current dominant practices on English teaching and issues of social justice that the report presumably wishes to promote.

9. There is a lack of specificity in the reporting in general. There are hardly any concrete examples of classroom practice and any exemplification is very vague. For example, the ‘How one school went about …’ sections are written in the broadest of terms that give no real indication of what a school was doing. These sections seem written to mirror what the flawed Ofsted English Research Review deemed to be desirable practice and could have been written without visiting an actual school.

Problems with exemplification run right through the report and, unfortunately, highlight a lack of subject understanding and knowledge in the writers. For example, in calling on schools to ‘make sure that the national curriculum requirements for spoken language are translated into practice, so that pupils learn how to become competent speakers’ the report recommends that ‘This should include opportunities to teach the conventions of spoken language, for example how to present, to debate and to explain their thinking’. In what ways are any of these three items ‘conventions of spoken language’?

10 There is a worrying lack of clarity and cohesion in the writing, and the thinking behind the writing, throughout the document. Here is just one example of many from the secondary section:

Learning a high-quality secondary English curriculum enables pupils to read increasingly challenging texts. This builds on the reading accuracy and automaticity that they developed at primary school. It is essential that schools devote time to pupils reading a lot of text, using background knowledge and vocabulary to explore literary texts in analytical and evaluative ways. Such a curriculum builds pupils’ readiness for future encounters with complex texts, critical views and ways in which we read in a disciplinary way.

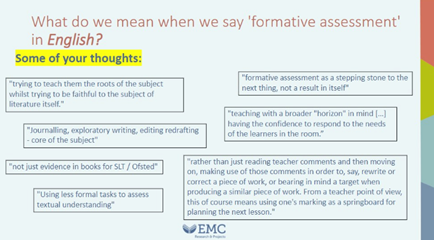

11. The report shows a concerning lack of understanding of assessment in English. Regarding formative assessment, it states that ‘Formative assessment focuses on looking at the component parts of the curriculum and checking how securely pupils have learned them.’ This is perhaps the clearest example of the disturbing reduction of the subject to its discrete functions. Over many decades research into assessment in English has concluded that it cannot be reduced to its component parts if assessment is to be meaningful. For example, Bethan Marshall and Dylan WIliam’s (2006) English Inside the Black Box points out that ‘formative assessment is considerably more than the sum of a series of handy tips and techniques’. Specifically on writing, Marshall and Wiliam comment:

the complexity of any given piece of writing means it is hard to itemise or predict in advance the features that might make it good except in the most general of terms…. Crucial to English teaching and learning, then, is the development of judgement. In this way assessment, which is, after all, a type of judgement, lies at the heart of the subject discipline. Any attempt at being more precise runs the risk of missing an essential ingredient.

12. We think it’s an odd thing for Ofsted to be telling Subject Associations what they should be doing, especially when they offer such a terrible directive about what they should be helping teachers to do – sequence, explicitly teach, identify the grammar and vocabulary that pupils need to be taught. This is a very narrow and partisan view of what teachers should be encouraged to do in English classrooms and is so far out of sync with all the significant research in the subject that it is not something that we intend to take seriously.

Conclusions

As stated at the start of this piece, the problems with this subject report stem fundamentally from it being entirely framed by the 2022 English Research Review. Even so, it seems curious that it was unable to reach beyond this mandate. The Ofsted inspectors must surely have seen other types of teaching going on, more in keeping with an alternative set of research-informed practices that are specific to the subject, rather than ones that are taken from other subjects and misapplied. We know from our own involvement with schools at EMC that they are being used and that they are often highly effective. We frequently see brilliant practice that does not conform to the ideas and practices foregrounded and given value in this document.

We know from the response to the critique of the 2022 English Research Review that there is enormous concern within the English teaching community about the subject and the directions it has been going in, as the result of ideas that have been strongly promoted, and continue to be promoted by Ofsted. Thousands of English teachers are fed up with the imposition from above of pedagogies that they know to be flawed. By all means, schools are welcome to teach to these pedagogies, but teachers also need the freedom not to be pressured into practices they don’t agree with because of feeling they have to comply with Ofsted’s limited, misconceived and partial view of what the subject entails and how they would like to see it being taught.