Dip into the whole cluster before looking at individual poems

Why not introduce the cluster of poems you will be teaching by looking at all the titles, all the first lines, or all the last lines? Ask students to speculate about the themes and some of the similarities and differences they might already be picking up about the poems in the cluster.

Teach comparatively from the start

Try teaching two poems side-by-side rather than teaching first one and then the other. Make a careful choice, so that one acts as a foil for the other, for example find two poems which have a similar theme or tone. Read the two poems aloud a couple of times and then ask students to start noticing similarities and differences. Doing this helps students to look beyond a simple statement of what each poem is ‘about’. For example, they might notice a difference in the shape of the two poems, or the fact that one is free verse while another seems more highly patterned, or that both are about a failed relationship but one poet seems to have come to terms with it, while another is still bitter. Circulate around the room and share good ideas or interesting thinking across the class. You might want to prompt them to look at different aspects of the poem, such as tone or voice, or whether it is more the expression of feelings or ideas. Once they have collected some good ideas, they should consider the reasons behind the choices each poet has made and what difference they make to the reader.

Build a personal response before asking for a critical response

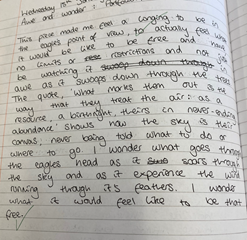

Sometimes we assume that students are engaging with and responding to a poem without explicitly encouraging that to happen. We start on analysis, a close focus on detail or writing structured paragraphs before they have many ideas of their own. As a result, students’ thinking tends to be superficial while they wait to make notes on the teacher’s interpretation and analysis. If we jump over the stage where they react, wonder, make tentative suggestions, or take wrong turns we are not building the personal response which is the foundation of a critical response, nor are we building the skills they need to approach poetry independently. A good first way in is to ask them to explore thoughts in an open-ended way. Students read the poem and ask themselves what sensations, images, feelings and thoughts they get from the poem. At this stage, the response belongs to the student and there are no wrong answers, so avoid stepping in with your own interpretation. Collect these first thoughts across the class and you may be surprised at how much material you have on which to base close analysis.

Use creative writing

If you recently attended the EMC twilight session ‘Making Poetry Meaningful’ with Peter Kahn and Christian Robinson, you will already be sold on the idea that writing creatively is a great way for students to find their way into a poem. We know that, for example, reading and writing persuasively go hand-in-hand, with one informing the other. But because it is not assessed in the exam, students tend not to get much experience in writing their own poems. In fact, getting them to write poetry is a really worthwhile exercise as making decisions as a poet yourself really helps when you come to look at the decisions another poet has made. Two possible ways in:

- Give students words and phrases from the poem before reading it and ask them to use these to make a poem of their own. When they read the poem these come from, they will be more alert to how they are used in their original context.

- Ask students to write an extra stanza ‘in the style of’. Ask them to do this before doing much work on the style of the poet as, in doing the writing, they have to pay close attention to things they may not otherwise be very aware of, such as tense, tone, and structure. Afterwards, debrief by asking them to reflect on what they had to do to try and make their stanza fit in seamlessly with the original.

Photo by yeongkyeong lee on Unsplash