The podcasts as a collection are extremely wide-ranging. Taken all together they demonstrate the complexities and possibilities to consider in developing oracy strategies for the English classroom and beyond. We highly recommend that you listen to the ones curated here as a starting point before diving into more! You can find the entire collection here.

Robin Alexander discusses how talk is at the very centre of education. He seeks to create a wider definition of oracy that expands beyond connections to the workplace, and to ideas around human development and democratic participation. Relating his thinking to the Russian philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin, he proposes that teaching with a focus on talk, can be distilled to the crucial question: ‘when a pupil speaks, what are we doing with it?’ He also discusses his personal experience of speaking to previous government ministers and opposition shadow ministers in trying to argue for dialogic pedagogy being at the heart of teaching.

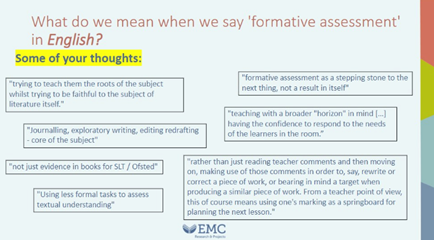

Barbara Bleiman outlines the key distinction between ‘learning how to talk’ and ‘talk for learning’, suggesting that episodes of dialogic learning, both in whole class discussion and peer talk, are central to learning in subjects. She talks about the processes of dialogue that allow students to think together, and so take learning forward, and the conditions necessary for that to happen. She considers oracy in English, what has happened to it historically and to the assessment of it in GCSE English and, as part of this, argues for a return to significant language study, in which students learn about spoken language. Learning about spoken language offers a linguistically sound basis for developing students use of language, and the way it is received by teachers. She argues that it is important for students’ voices to be heard, not just from the point of view of social justice and student engagement but also as a window for teachers onto their students’ learning.

Jeffrey Boakye speaks about how he sees oracy as inextricable to the politics of identity. He passionately discusses how society is set up to value middle-class ways of speaking, and that consequently, blind spots exist about how difficult life can be for those who have not been socialised into this dialect, for example, EAL pupils. On this point, he sees it as uncoincidental that a high percentage of young people in pupil referral units for example, have issues with their speech and language. His vision for an oracy curriculum is for the politics of identity to be taught explicitly, and for young people to discuss how spoken language is connected to how we judge people in our society.

Deborah Cameron speaks to Geoff Barton about how national education policy in the UK takes on a very predictable pattern: speaking and listening skills become a concern; there is a drive to embed oracy in the curriculum; this is then squeezed out by a political drive to go ‘back to basics’, with this always centring around reading and writing skills. She goes on to explain how this is due to an institutional need to evaluate and test skills, a process that struggles to incorporate oracy. She questions whether it should even try, critiquing assessment measurements such as ‘fluency’ and ‘being articulate’ as rooted in classism and being essentially vague and subjective.

Dr Ian Cushing details how ideas around oracy, and even the term itself, are connected to deficit models of education. He argues that educational institutions (and beyond) are so deeply rooted in prescriptive language ideologies, that the only solution is structural transformation. He also argues against narratives that tie solving social injustices to linguistic solutions, for example that ‘improving’ a young person’s spoken language will improve their life chances. For him, these narratives perpetuate ideas of language deficiency in working class and racially marginalised communities – and lay the blame with individuals rather than prejudiced institutions.

Rob Drummond speaks about seeking to find a definition of oracy that communicates to people who are outside of the world of the education. He highlights how from his socio-linguistic standpoint, the most important feature of spoken language is the way it connects to identity, be that in terms of our: race, ethnicity, social class, gender, or sexuality. He is also passionate about rallying against notions of ‘speaking properly’, and instead focusing on helping young people develop their voice authentically.

Michael Rosen speaks, in connection to the work of his parents, Harold and Connie Rosen, about how talk precedes writing, and is essential to understanding cognition. He sees classrooms as social spaces, where talking and listening allows pupils to explore their emotions and ideas in reaction to what they are reading, as they are reading (and not just once they have finished a book). He speaks about the ‘matrix’ he has constructed, which lists the types of ways pupils can respond to texts (e.g. asking questions of the text; speculating about what might happen; relating the text to lived experience), and about the varied ways teachers might facilitate their students’ discussions.

Professor Julia Snell talks about her research on the relationship between language and inequality, focused on talk in classrooms. She argues that the presentation of spoken standardised English in the National Curriculum has been highly problematic, prescriptively conflating this one form of spoken language with the ability to think and talk well. Assumptions, unsupported by the research evidence, about the relationship between spoken standardised speech and writing have also caused teachers to unnecessarily correct students’ speech. Her research focuses on dialogic talk in classrooms – talk to stimulate thinking and make thinking public. It shows how the policing of standardised spoken language can inhibit this and, in particular, discourage underprivileged students from participating in the kind of talk that has been shown to be very important to their achievement. She questions rigid, false dichotomies between formal and informal spoken language

Tom Wright approaches the idea of oracy from a historical standpoint. He takes the listener through a very interesting history of grassroots oracy education, such as 19th Century working class groups training themselves in speaking techniques in order to further their causes. He also details his work with the Speaking Citizens Project, which connects the idea of oracy to the media, culture and politics. Through his work with the project, he advocates for a civic form of oracy education that is less about displaying individual skill, and more about dialogue and exchange with people in real life situations.