It seems like a paradox. Critical writing is analytical, reflective, structured in terms of argument and evidence, planned, rule-bound, thought-through, high stakes, the main business of examinations. Creative writing is spontaneous, often semi-conscious or even at times unconscious, free of rules, personal, idiosyncratic, subject to the writer’s flair or talent, worked on over time, sometimes not shared with anyone else, often not highly prized (except if you’re entering for the Booker or the Forward Prize, or appear on the shelves of Waterstones), rarely examined as part of a literature course.

Of course, this characterisation is full of false dichotomies and stereotypes. For instance, if you stop to think, even for a moment, you realise that creative writing follows lots of rules – the conventions of genre, the expectations of audience, while critical writing of the best sort (hopefully much of what we publish in emagazine) has a strong, personal voice, breaks rules in order to bring ideas to life and is highly creative. But nevertheless, they are often perceived as distinct aspects of English as a subject, and are taught in isolation from each other.

There is a long history, however, strongly supported by EMC over the years, of bringing the two together, in recognition of the fact that not only are the boundaries blurred but also the two complement each other. The idea of ‘reading as a writer’ and ‘writing as a reader’ has been central to our CPD and publications on texts and critical analysis are always full of creative activities on literary texts. One aspect of our premise is that teaching about texts helps you to write – an idea at the heart of all Creative Writing courses at university-level, and confirmed by countless writers.

Stephen King, famously said:

If you want to be a writer, you must do two things above all others: read a lot and write a lot.’

and,

‘If you don’t have time to read, you don’t have the time (or the tools) to write. Simple as that.’

But the reverse is also true. Writing yourself helps you to understand better what other writers do. This might be discovering more about how a choice of narrative voice or point of view works, or learning more about a literary idea like symbolism, or it might be about discovering how a particular poem, or set novel, is using, adapting or subverting a style or convention, making it unique and special.

Creative writing to develop critical analysis does not have to be full-blown, time-consuming, all-singing-and-dancing, nor, if it’s carefully thought through in terms of purpose, need it be a distraction from ‘the real business’ of learning to write critical essays. It can consist of brief experiments, little playful try-outs – or what we call, on our courses and in publications, ‘micro-interventions’, where some small aspect of style and language is changed, to transform the text and see what the impact has been. (See Doing Close Reading.) So, for instance, one might try omitting all the adjectives and adverbs from a particularly rich passage from The Great Gatsby, to reflect on what the impact is, and by extension, what their effect was in the original. (Fitzgerald’s lush, over-abundant prose, juxtaposing romantic and modernist imagery, is created in large part through the use of adjectives and adverbs.) At GCSE, one could change the narrative voice at a key moment in A Christmas Carol, to move either into free indirect style, or away from it, to explore how Dickens directs our sympathies through subtle shifts in the third person voice. Ten or fifteen minutes on this kind of activity can pay off in terms of students getting under the skin of the writer’s craft. ‘We haven’t got time for nice things like that,’ isn’t an argument if ‘nice things like that’ actually teach ideas about the writer’s craft really well.

Reflecting on what’s been learned by doing creative writing around texts is vital. It’s fun to try writing yourself, or make changes to a text, and, of course, it has its own independent value but in the end, as part of critical analysis, the key point is to understand what you’ve learned about the text under scrutiny.

One example

Here’s an example of me testing this out for myself. I did it alongside teachers on a recent course, using a short extract from Jane Eyre.

The extract from Jane Eyre

‘What dog is this?’

‘He came with his master.’

‘With whom?’

‘With master – Mr Rochester – he is just arrived.’

‘Indeed! and is Mrs Fairfax with him?’

‘Yes, and Miss Adele; they are in the dining room, and John is gone for a surgeon: for master has had an accident; his horse fell and his ankle is sprained.’

‘Did the horse fall in Hay Lane?’

‘Yes, coming down-hill; it slipped on some ice.’

‘Ah! Bring me a candle, will you, Leah?’

Leah brought it; she entered, followed by Mrs Fairfax, who repeated the news; adding that Mr Carter the surgeon was come, and was now with Mr Rochester: then she hurried out to give orders about tea, and I went upstairs to take off my things.

My microintervention – changing dialogue to narrative voice:

I asked Leah about the dog and whose it was. She was slow to respond, infuriatingly so, as I had already recognised the dog and was in a state of high anxiety, wondering how on earth its owner had ended up in the house. Finally, she told me that it was Mr Rochester and that he had had an accident. Of course, I knew that it was the man I had helped but still I couldn’t refrain from confirming that it was definitely him, and then discovered to my shock that it was none other than my master, the owner of the house.

Exploratory thoughts on my creative writing experiment

I’ve discovered that the use of dialogue only leads to the absence of any exposition of Jane’s feelings. This creates an extra frisson of anxious excitement. I was fully aware of Jane’s shocked discovery of who Rochester was, though Leah wasn’t, and of how she carefully disguises her agitation. The lack of description of her emotions paradoxically makes her likely inner turmoil all the more heightened. We are also with her in the moment of discovery, rather than hearing about it retrospectively, as in my example.My critical writing as a result of reflecting on the creative writing experiment

Through the use of dialogue, Bronte heightens the moment of Jane’s discovery that the man she helped in Hay Lane is in fact Mr Rochester. The lack of narrative explanation first has the effect of the events unfolding for us as they do for Jane, in the moment, and without any retrospective reflection. This makes it more immediate and dramatic. At the same time, it means that Jane’s feelings are withheld from the reader. All we have is the words she uses to Leah, with no explanatory speech tags, indicating her reactions. She is forced to keep the exchange entirely emotionless, yet as readers, we read into this her shocked realisation and recognise that this is a highly charged and significant moment. Her factual account of going up to her room, at the end, suggests her need to recover from her agitation, without revealing this to Leah or anyone else in the household.

The whole process took about twenty to twenty-five minutes. (Obviously for students this might be a little longer.) Like me, the teachers who try this kind of approach on our courses tell us that it gives them real insight into the text and would be very beneficial in terms of students’ ability to write about passage-based questions in exams, and in teaching them about how literary texts work.

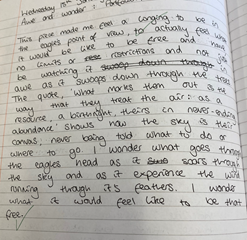

The evidence? Brilliant critical writing at GCSE and A Level

As I’m suggesting, we have long been convinced of the value of these kinds of approaches to critical writing. But something happened recently to absolutely confirm this for us. The Forward/emagazine Student Critics’ Competition, which has run for the first time and has recently been judged, had three entry groups (14-16, 16-19 and teachers) and two categories, Critical and Creative-Critical. Lucy Webster and I, as editors of emagazine, did the initial read-through of entries, before passing the shortlist on to Sarah Howe, a poet/critic whose own view of reading and writing as complementary acts is very much in line with our own thinking. The quality of entries, in both the 14-16 and 16-19 age groups was exceptionally good in both categories. But what was particularly startling was the extraordinarily high standard of the creative writing and the critical commentaries that went with it. The students who chose this option not only commented with critical acuity about their own writing but also wrote brilliantly about the poem that stimulated their own work. Both at 14-16 and 16-19, it was very clear that there was a depth of insight, freshness of response, clarity of thought and personal, critical voice that were, at times, quite remarkable. These GCSE and A Level students were doing in their critical observations, exactly what the GCSE and A Level Literature examiners’ reports say they would like from students – fresh observations, talking about what’s significant, writing concisely and with relevance, thinking independently, showing depth of knowledge of the text. This link takes you to the winning entries.

Not only at GCSE and A Level, but long before that, at KS3, (and well after, at university level), critical analysis can be enriched by students writing themselves. As the Forward/emagazine winners show, it gives them a lot to say about texts, and the kinds of things they have to say are grounded in a strong sense of how writing works and genuine ideas about what writers are up to. It’s not a lovely little optional extra, but one of the strongest weapons in our armoury, a really powerful way of teaching critical analysis.

Further reading

At university-level, there is a long tradition of creative-critical work and a recognition of its value:

1. Active Reading: Transformative Writing in Literary Studies, by Ben Knights & Chris Thurgar-Dawson (Continuum Literary Studies)

2. Textual Intervention – Critical and Creative Strategies for Literary Studies by Rob Pope (Routledge)

3. Catherine Maxwell: Teaching Nineteenth-century Aesthetic Prose: A Writing-Intensive course, Arts and Humanities in Higher Education 9.2 (2010), 191-204

4. The work of Lucy Newlyn, incorporating creative writing into literature work with students at Oxford University, described on her website page.

Writers on reading literary texts from a writer’s perspective:

1. Reading Like a Writer: A Guide for People Who Love Books and for Those Who Want to Write Them by Francine Prose (Union Books)

2. 52 Ways of Looking at a Poem by Ruth Padel (Vintage)

3. Strong Words: Modern Poets on Modern Poetry ed. W.N. Herbert (Bloodaxe)

Sarah Howe has founded a website called ‘Prac Crit’, which brings together critical discussion of poems with interviews with the poets, exploring ideas and processes in their writing.

Last but not least, Chapter 8, ‘Critical-creativity’ in our very own Andrew McCallum’s book Creativity and Learning in Secondary English: Teaching for a Creative Classroom (Routledge)