I was lucky enough recently to be invited to Alexandra Park School in North London to observe how the English department is approaching talk. The six lessons I went into were brilliant. There was plenty of talk, of course, but also good behaviour throughout, lots of learning, and enthusiasm in bucketloads.

The lessons were a real endorsement of the current drive to get more talk into classrooms. As I moved from room to room, what I observed was clearly the very stuff of English: students learning through discussing material carefully selected by the teacher; prior learning being reinforced through talk and new knowledge being generated; the teacher pushing students to develop their spoken responses further and filling in gaps where needed; students being exposed to multiple ideas in a short space of time; well-managed, collaborative group work creating a sense of unity; students eager to get on with the lesson and having fun.

Lots of schools are currently embarking on similar journeys, so it made sense to write up some notes about the good practice that I saw. Talk has been neglected at policy level for quite a long time now, so if you have a sceptical SLT, or you simply need a refresher about the value of talk and how you might approach it in your classroom, then hopefully there are some useful pointers in what follows.

Talk encourages deep thinking

In each class students were grappling in different ways with conceptual ideas linked to the texts they were studying. Whether they were wrestling with the concept of leadership in Lord of the Flies, or masculinity in Much Ado About Nothing, they had to think hard, and think for themselves, in order to have something to say.

Talk works well in mixed attainment classrooms

All the classes I observed were mixed attainment, with a wide spread of levels, but there was no sense that some students were struggling, largely because the talk activities had been carefully planned using ‘low threshold, high ceiling’ strategies. All students could step into the tasks, but they could also extend their thinking to a level that was appropriately stretching for them. For example, in discussing masculinity in Much Ado, students were given a list of statements. They had to choose the three statements they found most interesting, a straightforward task to set up and complete, but one which enabled deep thinking. Pairs in a Year 7 nurture group studying Sawbones by Catherine Johnson worked their way through a series of questions. Building an agree/disagree element into some of the questions generated a real buzz among the students, who developed ideas well beyond what I suspect they would have managed if set to write responses to the same questions.

Exploratory talk prepares students for close reading

The Year 7 students moved on from their discussion work to a short writing task. They were asked to select and write down quotations to back up their thinking about one of the characters in the novel. They were willing and able to do this task (one which I regularly see students reluctant or unable to complete) largely because their discussion had developed their knowledge and understanding of the novel. They’d talked into existence a context on which to pin their quotations. The six lessons I observed didn’t build towards substantial writing in the time I was in the classroom, but there is every reason to believe that talk activities like this are also excellent preparation for writing. We know this from other classroom work we’ve seen, such as in our group work project, and the work of the seconded teachers at EMC last year and the current Associate Teachers.

Exploratory writing prepares students for talk

In a second Lord of the Flies lesson, students had written personal reflections about the chapter they had just read. They then read each other’s work in groups, writing what they noticed on post-its. Each group then discussed patterns they found across their work and fed this back to the whole class. In doing this, they not only developed their understanding of the novel, they also got to experience different ways of reading and reflecting on novels in general. Explanation and self-explanation are key to extending and consolidating understanding. You could hear real pride in the voice of the first student to offer her findings to the whole class about patterns across her group’s work: this was what they had found out. This was their thinking about the novel. There were still, of course, plenty of opportunities for the teacher to fill in any gaps if needed.

Talk aids memorisation, reduces cognitive load

In all the lessons it was clear that talking about their reading reinforced understanding and cemented knowledge. Additionally, it generated new knowledge, which inevitably emerges in any well-structured authentic dialogic exchange. In the discussions that drew on the statements about masculinity in Much Ado, for example, students had to recall key moments in the play so that the statements made sense and were contextualised. Doing this through informal exploratory talk also reduced cognitive load. All the focus was on recalling knowledge, not the form of recall, which can dominate and get in the way of knowledge development. This is an important point. Bizarrely and frustratingly, many of those promoting a ‘knowledge-rich’ curriculum over the past decade or so, also denigrated talk and group work, so limiting what could be remembered and the new knowledge that could be generated.

It's helpful to build up to whole class discussion

I saw moments of valuable teacher-led talk in every lesson, sometimes with the teacher fully involved in the discussion, other times directing students to provide their own comments, but without adding anything of their own until the end of the discussion. This worked best when talk had been staged gradually. For example, students might write down some of their own reflections, then discuss these in groups, then share their ideas as a whole class. Where the group stage was missed out, students were a little more hesitant and their ideas not as fully formed.

Talk sentence starters have their place

We’re quite wary of talk sentence starters at EMC, particularly where students are learning through talk. They can get in the way, blocking thought processes (cognitive load again!) and making students sound stilted and inauthentic. They can, however, help focus talk in particular ways. For example, in the first Lord of the Flies lesson I observed, talk sentence starters were used to ensure students listened to other comments before providing their own in their discussion of leadership in the novel. After listening to a comment, the next student to speak might start with ‘I generally agree with what you’re saying, but …’; or ‘That’s absolutely what I was thinking about when …’. Ideally, students would eventually have no need of starters like these, instead able to come up with different ways of recognising and building on previous comments on their own.

Students respond differently at different ages

I was lucky enough to go into lessons for all five KS3 and KS4 age groups, which gave me a very clear sense of the way that students respond to talk activities at different ages. Year 7 seemed to be the easiest to get going, with their ready supply of enthusiasm and lack of inhibitions. Well-designed, engaging tasks meant there were no problems in getting Year 8 and 9 fully engaged in talk either. The Year 8 Macbeth lesson culminated in students acting out one of the witches’ scenes. The students loved the opportunity to engage fully with the play and you could sense that they were building their ability to handle the difficult language, even where they did not fully understand it. Year 10 and 11 required more cajoling to get going, particularly when giving responses to the whole class. They were harder to hear, often too self-conscious to project their voices fully, and less keen to volunteer. Preparatory group work really helped in the second Year 10 Lord of the Flies lesson, providing students with opportunities to rehearse ideas in a non-threatening way. A Year 11 Romeo and Juliet lesson relied largely on the teacher leading the discussion. It worked really well, the teacher drawing on lots of students for responses and moving at a quick pace. It seemed like a sensible strategy for this particular class, at this particular stage.

Statements are a rich resource for talk

One common anxiety about using classroom talk is that it leaves students in a vacuum, recirculating their existing knowledge, but not adding to it. This is slightly erroneous when looking at a text. Basic reader-response theory tells us that new knowledge comes from reading and discussing the text itself. However, students might not be able to generate enough ideas, or to push their thinking to new levels on their own. Statements can really help cement existing ideas and generate new ones. The statements, in a way, are the knowledge. Discussing them, ordering them, selecting from them, requires engagement with that knowledge and also builds on it. The statements used to explore masculinity in Much Ado were particularly interesting, as they had been generated by the students themselves as part of their homework. They had a real stake in the activity, then, when selecting three that they found interesting.

Talk activities help with behaviour management

Because the activities I observed were well-designed, accessible and engaging, while also offering plenty of challenge, students were eager to get on with the work. I saw far fewer examples of students reluctant to work (in fact, I can’t remember seeing any) than when I observe lessons chunked up into small sections, mostly involving bits of tightly directed writing. Consequently, there were no issues with behaviour, with teachers able to circulate around the class freely. (This was also a finding of our group talk project, where teachers reported improved behaviour.)

Talk can save planning time

It’s important to stress that everything I observed was carefully planned and resourced, the teachers being highly knowledgeable about the texts under discussion. However, most of these activities drew heavily on students’ own initial responses to texts, so removing the need for the teacher to design any bridging resources. Once students had generated ideas through talk, these could then be built on, either through specific resources, but also through combining ideas with other students and the teacher.

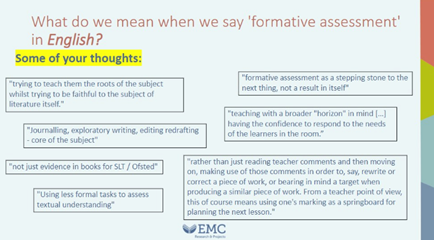

Talk is useful for formative assessment

Every time a student spoke, the teacher was able to evaluate their level of understanding of the material they were working on, adding to their bank of knowledge about that student. They were also able to evaluate how the whole class were responding to a text or activity, based on the different responses being generated. Talk gave them a window into learning that would allow them to both evaluate student understanding and be responsive in next steps.

You have to trust in outcomes over the long term – and the evidence is there

In all the lessons observed, students were building on prior knowledge and generating new knowledge. Attempting to assess this quantifiably for each student within a single lesson would have been very difficult and, in truth, fairly pointless. While such an approach goes against the grain in an objectives-driven culture, teachers can be confident in trusting that regular use of talk in English will develop their students’ learning. The evidence is there, too. A 2022 report by researchers from the University of Bristol, funded by the Nuffield Foundation, for example, looked at what classroom activities were most linked to successful GCSE outcomes. They concluded that “the most important activity for English teachers appears to be facilitating interaction and discussion between classmates; more time spent on this tends to raise English GCSE scores.”

My time spent at Alexandra Park was genuinely inspiring and filled me with hope for the future of the subject, now that talk is firmly back on the agenda. The six lessons reminded me that, as English teachers, we’re in the language business and the thinking business, with the two inextricably linked. We display our thinking through language; using language develops our thinking (to paraphrase Vygotsky). The easiest, most immediate, most obvious way to do this is through talk. Stifle talk and you stifle thinking. Stifle thinking and you stifle learning. So here’s to English classrooms everywhere promoting talk and so promoting thinking and so promoting learning!

Thanks to all the teachers at Alexandra Park School who welcomed me into their classrooms. Special thanks to EMC Associate Teacher, Lauren Cowan, for organising the visit and to Lucy Strike, lead teacher for oracy, for her time after the lesson observations.

Further reading

EMC: It's Good to Talk Project

We Need to Talk 2024: Oracy Commission Report