Noticing is a powerful tool when studying literary texts and language in general. It’s something that has been used at the English and Media Centre for many years, particularly when studying poetry. A great starting point to encourage personal response is simply to ask students what they notice about a particular poem. This might be in very general terms, or it might be that teachers direct students to comment on what they notice about something specific. What do you notice about the way this poem is structured? What do you notice about the poet’s use of voice? What do you notice about the rhyme in this poem?

It’s a tool that can extend beyond literature. Fiona English and Tim Marr, in one of the best books about language that we’ve read in recent years, Why Do Linguistics?, call on their readers to be constantly vigilant to what they notice about the language around them. Their own ability to do this forms the starting point for much of the work in their book.

And recently Tim Taylor wrote an interesting blog explaining how students can be encouraged to notice things in a painting used as stimulus material in a history lesson. It was written, in part, as a gentle reminder that the knowledge, inquisitiveness and curiosity that young people bring to any text means that they are capable of interesting responses without excessive intervention from the teacher. Once the ‘noticing’ period is over, the teacher can then judiciously contribute additional knowledge as necessary.

Noticing seems to be a particularly useful approach when encouraging students to recognise that much of the contextual knowledge that they need to know about texts is contained within the texts themselves. Yes, I do need to know something about mid 19th century England to understand A Christmas Carol fully, but I can understand it as a story without this knowledge, and I can pick up an awful lot about the context of the time simply by reading it. How else would Dickens be remembered as the greatest social commentator of his day, if not by detailing the society in which he lived? So, just by reading the novella, I can notice the significance and form of Christmas as a time of celebration in the 1840s. I can also recognise the poverty that afflicted much of the population, but which sat alongside extremes of wealth and a general sense that there was enough to go round for everybody. I can notice certain expectations of charity from the better off and the power and fear exerted by money in equal measure. Young readers are perfectly capable of noticing these things too, even if they might not articulate them in the same way.

Allowing students to notice context first, before providing them with additional information, means that their understanding of the social and historical events dealt with by a text is absolutely rooted in the text itself. The danger of approaching study from the other way round is that they latch a decontextualised piece of knowledge on to a text with no real sense of how it applies. It also limits the knowledge that they have. If they are presented with five to ten bits of information before they even read the text, then it risks blinding them to noticing anything else.

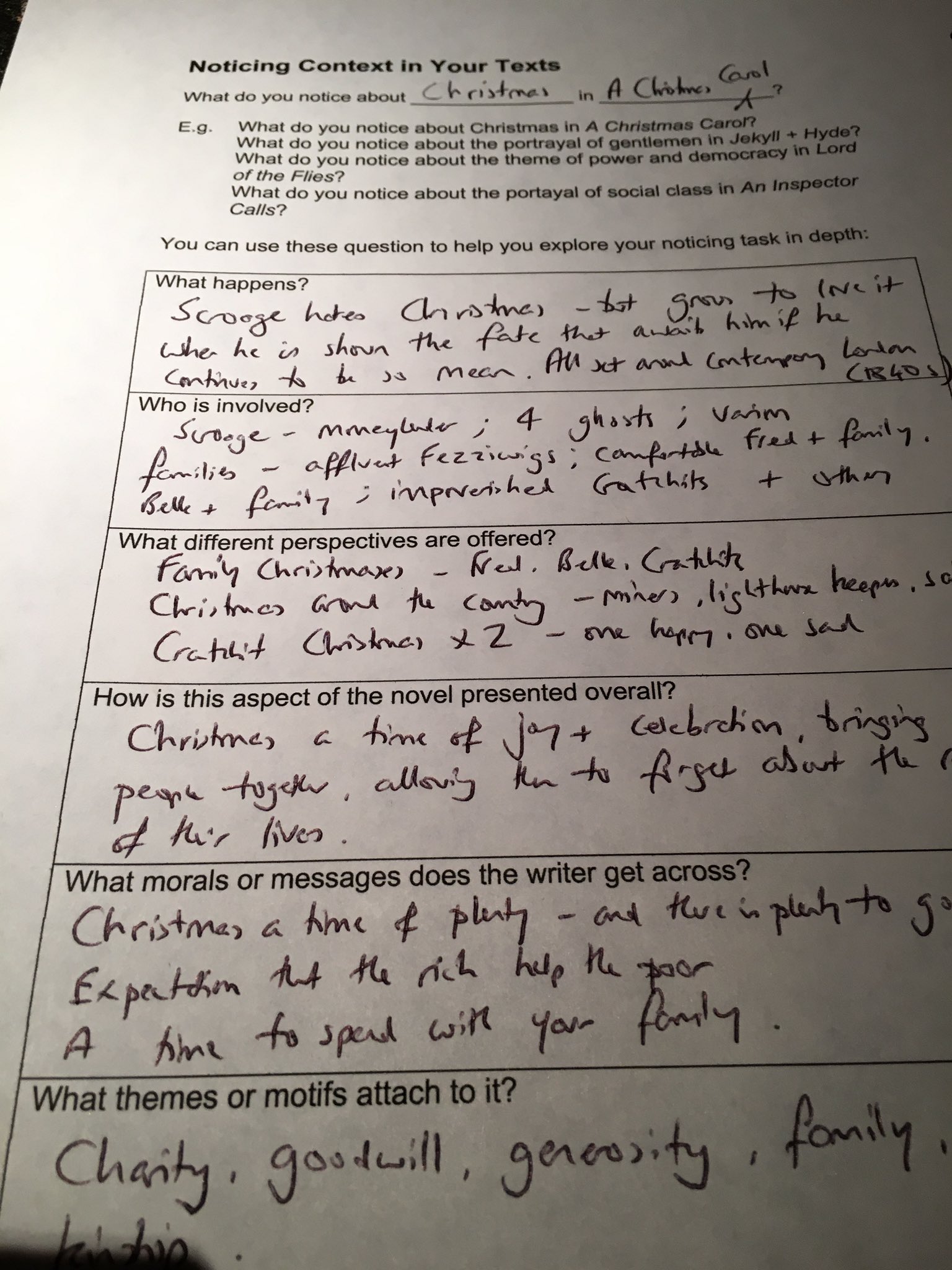

Using noticing like this as part of a revision programme works particularly well. Students will be familiar with a text from their initial period of study (and presumably have a pretty good idea about the significance of context already); they can begin revision by recording everything that they notice afresh and remember about context from re-reading, or general recapping. To give this structure, teachers might like to use a grid like the one here. Only when students have completed the grid, drawing on ideas from classmates and the teacher, do they look at additional information (as exemplified in sheets 2-5 on the exemplar link). Approaching the work this way round means that the students are much more likely to foreground the importance of their source text, applying social and historical detail in meaningful ways. It makes sure English really is English and not a weird sub-strand of History.

The grid used in the example here can be used with any other text. For those of you not teaching A Christmas Carol, additional contextual points have also been provided in the exemplar material in response to the questions about An Inspector Calls, Lord of the Flies and Strange Case of Jekyll and Hyde. The work comes from one of our two new download publications for GCSE revision, versions of which will be available for every relevant awarding body at the start of February.