Genuinely useful peer and self assessment can be difficult to achieve. Students often struggle to know what to say about their own or another student’s work. Comments they do make are often quite basic and, when looking at writing, can tend to focus on how something has been written without paying particular attention to content.

Chloe at John Stone Community School* and James at Kiteford School, who were the lead teachers for the EMC assessment project, both recognised the value of self and peer assessment and the difficulties in getting it right. Chloe acknowledged that meaningful self and peer assessment needed regular practice and clear set-up from teachers, and that it had suffered in her school post-pandemic. She explained during our pre-project meeting:

From [the] Covid hangover, I noticed that self and peer assessment was difficult...they didn’t know, necessarily, how to do it, I don’t think that we as a department had a singular strategy, how to even teach self and peer assessment, how to respond to their own work... we’ve been really pushing on that this year.

She recognised that simply doing self and peer assessment wasn’t enough: thinking carefully about how to teach students to do it was a pre-requisite for its success.

In James’ experience, students at Kiteford were familiar with self and peer assessment, but were quite fixed in how they approached it. They were routinely using What Works Well (WWW) and Even Better If (EBI) to give comments to peers, but not necessarily thinking deeply about the actual content and purpose of those comments. He had been thinking about how to improve this before starting the project:

When I’ve previously been doing peer and self assessment it tends to have been WWW, EBI and where I’ve tried to improve that in the past has been to provide some examples of good comments to help students move on from just like “write more” or “I like your handwriting”.

Positives and problems with asking for student comments

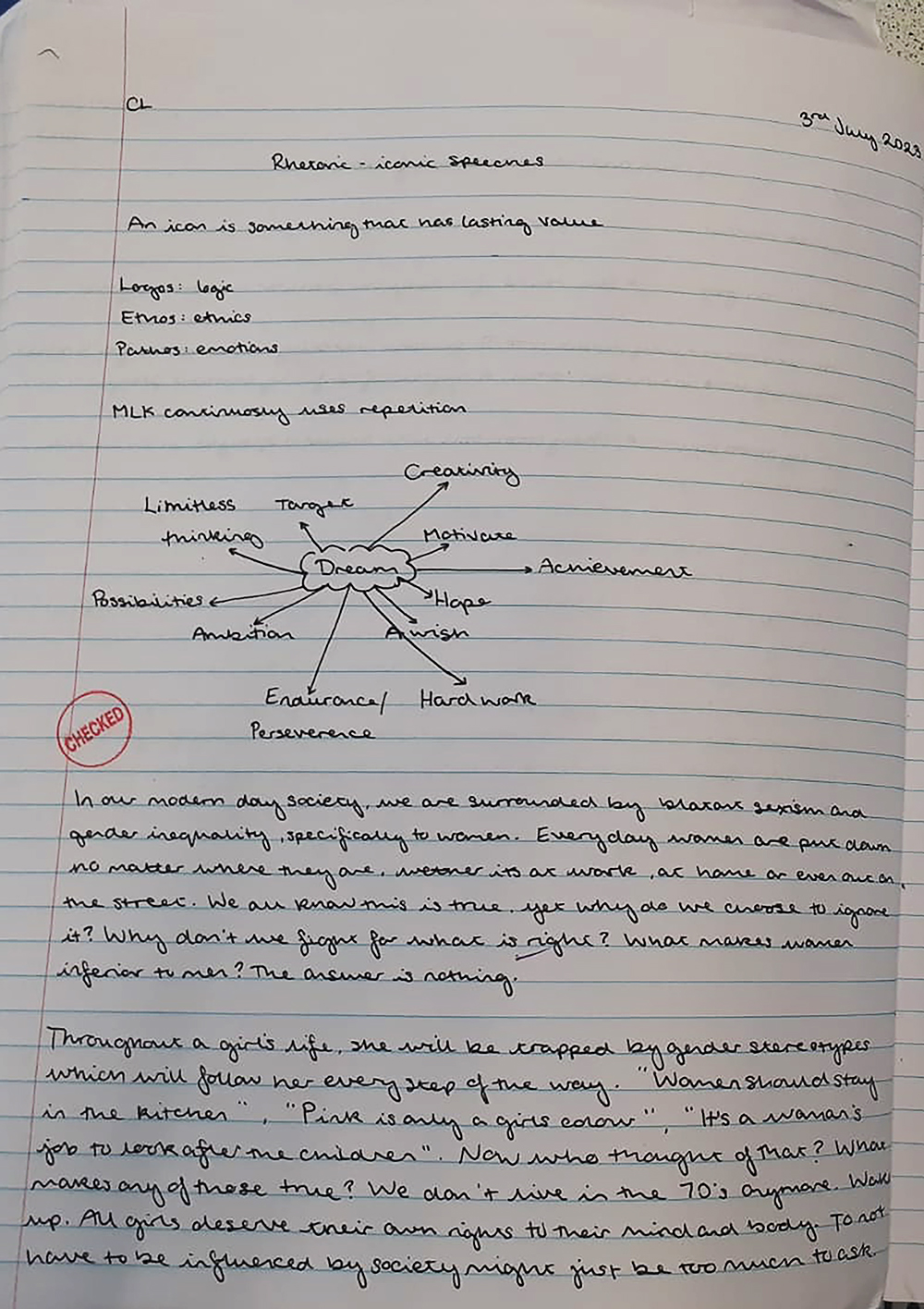

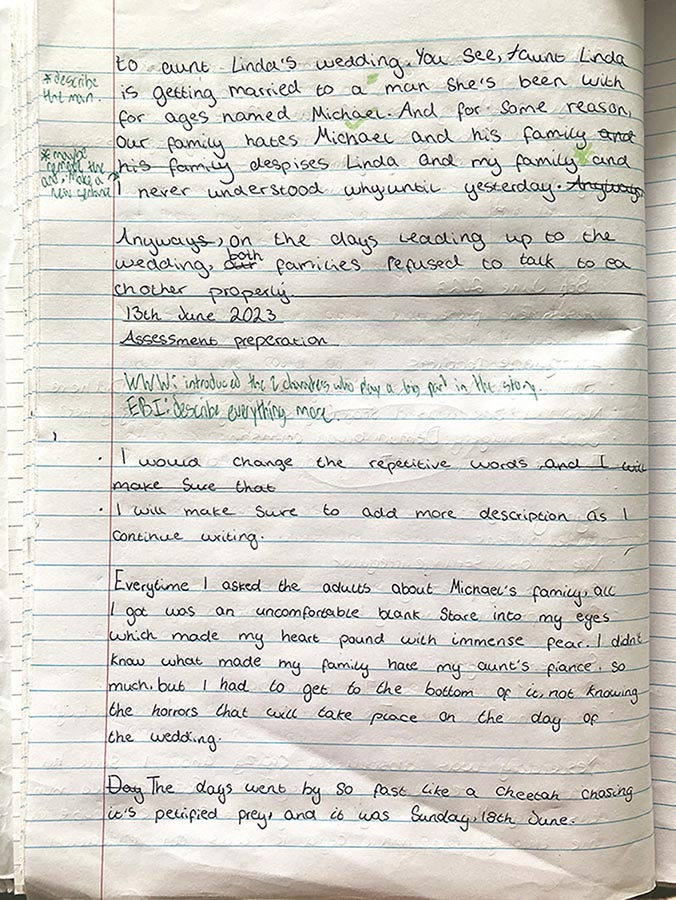

When we reviewed students’ work from the project unit, we noticed that students in both schools seemed more confident when they gave their peers positive comments than when they attempted to advise on next steps. Here is one example from Kiteford:

Example A, Kiteford School

In this example and in others that we saw, the student’s ‘WWW’ comments suggest genuine interest and enthusiasm for their peer's ideas: ‘I love […] referring to your own experience’. The comments in this book and others, though, while authentic and positive, were still relatively light. Interestingly, the same students struggled to give ‘EBI’ comments with any sense of authenticity and confidence. In A, the student was told their writing would be better ‘if you wrote more’. In another example, a student suggested that their classmate should ‘add rhetorical questions and maybe facts’. These kinds of light responses were replicated elsewhere in the class.

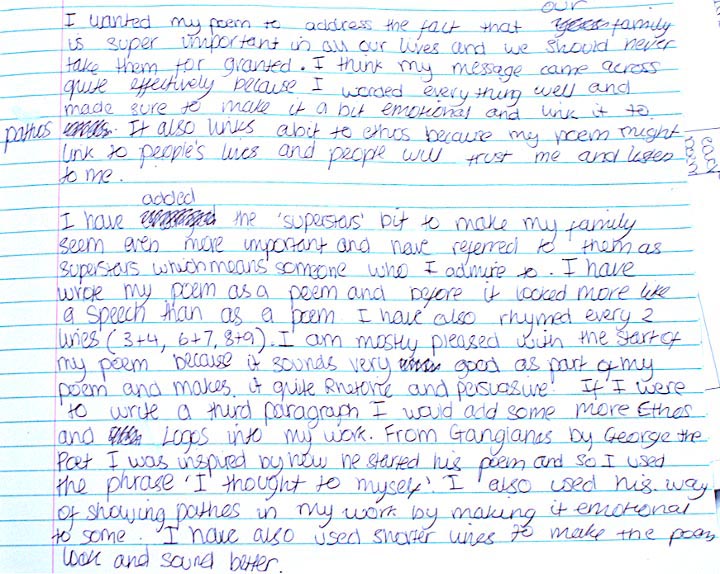

Similarly, at John Stone, students struggled to articulate what to do next both in their own work and the work of others. In Example B, ‘describe the man’, ‘describe everything more’ and ‘add more description as I continue’ are vague aspirations and don’t make it clear what impact these changes would have, or why they’re important.

Example B, John Stone Community School

It’s no surprise that students made such vague comments. Feedback is a difficult enough process to get right as a teacher. Perhaps we shouldn’t get too hung up about this. Reading back on their own writing and evaluating other students’ work is a process that in and of itself is likely to help students to develop their understanding of how writing works and to make judgements about the relative quality of different pieces.

But are there more effective ways of asking students to self and peer assess work? What happens, for example, when students are not directed to assess a piece of work using the forms of response that a teacher would draw on in their own work, but instead focus on their response as a reader or a writer? (asking questions like, how did you feel when you read this piece? or, which parts made you feel strongly, and why?) James, at Kiteford School, experimented in just this way with a self assessment strategy.

Positioning students as writers: a breakthrough!

We mentioned earlier that before the project, James had tried giving students a range of comments to choose from when they were self and peer assessing as a way of structuring the process and avoiding the ‘write more!’ issue. During the project, he rethought this strategy and tried something else: framing self assessment as a series of writerly questions to help students interrogate their own process and think deeply about their work. He offered the following prompts to help students respond to poems they had written in response to ‘Ganglands’ by George the Poet:

James' prompt questions for poetry commentary

-

- What did you want to achieve in your poem? What was the message or advice that you wanted to communicate?

- How effectively do you think your message comes across in your second draft?

- What inspiration did you take from ‘Ganglands’ by George the Poe? Can you give examples from your own work of how you used his as a guide?

- What are you most pleased with in your final draft? Provide specific examples of words/phrases/lines and explain why.

- What did you change between your first and second drafts, and why? Provide specific examples and explain why.

- If you were to write a third draft, what would you still like to improve or change? Why?

- How effective do you think your poem is as a piece of rhetoric? Why? Does it link to logos/pathos/ethos?

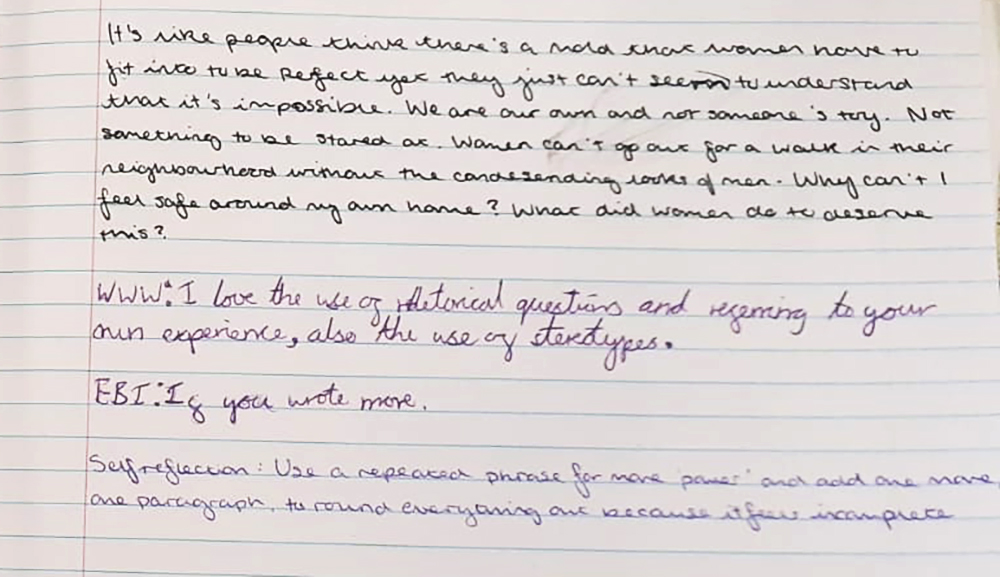

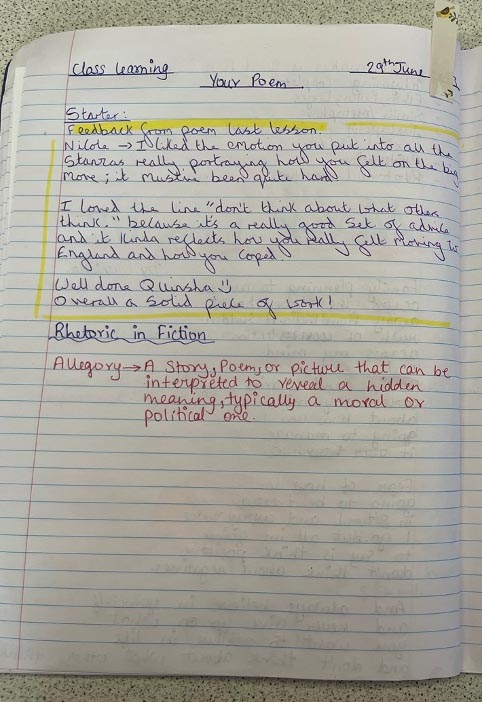

Here is one example of a student's work:

Example C, Kiteford School

This approach seems to have helped this student to engage with their work at a much more thoughtful level than when asking them to make up a comment themselves or pick an option from a pre-selected range. Giving students a comment bank to pick from is a well-meaning scaffold; it models the sorts of comments teachers might make on a piece of work and helps students avoid giving unhelpful feedback. But it doesn’t encourage students to think hard for themselves. The questions that James posed his students allowed them to review the writing process and their ideas to evaluate their success.

Example C is genuine and personal. The student has made the connection between the emotion and message they wanted to create, and the means they used to try and create this. They showed a growing understanding that their choices as a writer influence the response of their readers. The questions have encouraged them to reflect on really significant aspects of audience, purpose and form. It’s a lovely example of the way well-managed self and peer assessment can help students narrow the gap between their own work and the work of other writers.

James reflected that this approach worked better than his previous attempts because:

I think [the questions] are broad enough but also focused enough. You know… number 4 is just “what are you most pleased with” and we spoke last time about it not being the best thing, but what do you like? And make it more opinion based, but then, provide specific examples. Honing in, and make them analytical. […] The best thing for me has been giving them a whole series of questions and forcing the reflections to be paragraph length rather than just sentences, giving over a whole portion of the lesson to them reading and developing their own responses […] The quantity is far more in depth than we normally get.

James recognised that this way of doing things helped his students to position themselves as critics of their own writing: selecting the parts of their work that they personally responded to and justifying this robustly using evidence. Giving the process time and space - ‘a whole portion of the lesson’ - and having high expectations for the level of detail and thought in the reflections - ‘paragraph length rather than just sentences’ - was also key for enabling the full range of students in his class to access the task and articulate their ideas fully.

Developing self and peer assessment: a disciplinary decision

Vachana at Kiteford School was already using peer assessment routinely in her practice before the project. We interviewed her after the project to ask how opening up space for meaningful formative practice in the classroom helped her to develop her peer assessment strategies. What happened when she had more time to do the kind of teaching she instinctively felt was valuable, without the pressure to 'get to the end' for the summative assessment? She commented:

They were able to give each other feedback and do some self-reflection on that feedback even. I haven’t done that before.

I have made it that you’re reading three people’s work. You’re not just reading one person’s work. You’re reading two or three people’s. And then you’re making a decision on what did you like about each one of those. Takes a lot longer... and going ‘oh I like that one and I like that one but I also like this one’... can I combine them?

Like James, Vachana reflected on the issue of time. She thought that investing class time in the process of peer assessment was valuable for her students because it gave them opportunities to see a variety of interpretations of a task, make evaluations of their quality and bring this back to their own writing.

She also reflected on the difference between criteria-based assessments and engaging students in much more active and critical 'judgements' during self and peer assessment and the implications this has for English teachers:

Not having a strict success criteria has been interesting. Because I’ve just simply said ‘how is it reflecting Martin Luther King’s speech?’ and they’ve come up with ‘oh but you know in hindsight I should’ve used repetition a lot more and I haven’t done that... maybe that just kind of shifts the focus, it’s not as positive as it could have been.’ They are able to make those judgements on their work or on their peers’ work which has been good. [It] also shows teacher mentality because for so long we have focused on technique rather than focusing on the ideas and our emotions, with our feelings, even sometimes with our senses – how do we respond to a text? We are not teaching that enough.

Below you can see an example of peer assessment from one of Vachana's students that focuses strongly on the reader's emotional response to the writing and through this offers genuine and thoughtful engagement with the ideas of the piece:

Reflections and takeaways

Moving away from the dominant assessment model of heavily scaffolding all students towards the same final assessment piece allowed the project teachers a bit more time and space for thinking critically about their use of curriculum time. Without the model in place, our feeling is that feedback in all its forms became integral to curriculum in both the project school units: it drove the sequences in the classrooms. The evidence of self and peer assessment we’ve seen has shown us that through the project teachers developed a more intuitive sense of when – and what kind of – feedback would be most useful for their students and that students were developing a better sense of how to judge their own work.

We’ll leave you with our top 5 takeaways for using self and peer assessment meaningfully in English:

-

- Focus students’ comments on what is there, not what’s missing.

- Respond as a reader to the writing: how does it make you feel/think/respond? When? Why?

- Support students with questions, not comments – don't tell them what to say, show them how to think.

- It takes time to do well - both inside lessons, and in terms of a period of persistence and experimentation – and it won’t always work. Play the long game.

- Keep experimenting – for example, combine self and peer feedback, get students to read multiple students’ work – to prevent students becoming disengaged in the process.

*All school and teacher names in this blog have been anonymized.