In our previous blogs, we’ve outlined the dominant assessment model for English currently in place in many schools across the country, unpicked the wide-ranging implications of this model for the subject, and introduced the two project schools that wanted to try out our research questions and investigate an alternative to the dominant assessment model. A reminder of those research questions before we go on:

- How does formative assessment work best in English classrooms?

- What is the relationship between formative and summative assessment in English?

And sub-questions:

- What happens when students spend more time reading, writing and editing their work in English?

- What happens when English teachers have time to read and respond to student work?

- What happens when English teachers moderate and standardise KS3 work together regularly?

- Are there barriers to using formative assessment effectively in the English classroom?

- What happens when a single piece of assessment is removed from the end of a unit of work?

- What happens when a range of student work is used to summarise student attainment in English?

In blog 3, we showed you what the two project schools decided to do: they really recognised the shift that removing a single piece of assessment might make in allowing them to explore the relationship between formative and summative assessment in English. Both schools were working on writing units. At Kiteford Senior School*, this was a brand-new rhetoric unit. At John Stone Community School, it was a re-worked short stories unit. In both schools, these units would have traditionally been organised around a ‘formative assessment’ piece somewhere in the middle of the unit, and a similar ‘summative assessment’ piece at the end, which would be assessed and reported on as data. During the project, when this structure was removed, teachers felt more able to plan for variety, creativity and a range of written and spoken activities. The effect on student writing was significant. Students were able to display more creativity, respond authentically, write more and produce a range of responses that provided valuable, authentic assessment material for teachers to work with. Below is an outline of each of these key findings.

Students were able to be more creative

We found that, on the whole, writing in students’ books was much more experimental and creative. Offered more freedom to complete work using their own ideas, with guidance from teachers, students generally responded with enthusiasm and took risks. Books were sometimes messier, with more scribbling out and more drafting, but this was in keeping with the writing process. We feel this is much more valid for the subject discipline and teachers’ ability to formatively assess, respond to and challenge students than the alternative of a single piece of tightly scaffolded written work such as the example we looked at in blog 2.

Click here for some examples of the range of creative writing activities students did in Kiteford’s rhetoric unit (outlined in blog 3) from across the year group. Below, we discuss the subject knowledge and skills demonstrated in some of these pieces.

Poetry as rhetoric

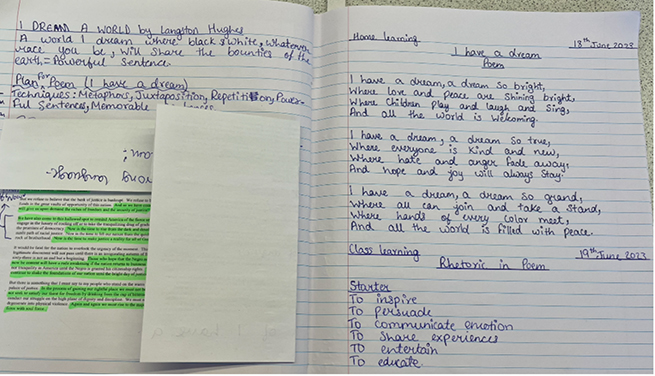

One of the examples we’ve selected is a student recreating Martin Luther King’s famous ‘I have a dream’ speech as their own poem. The teachers wanted to explore the relationship between the forms of speeches and poetry in terms of language, purpose and effect. These poems were really interesting to the teacher, as the students are handling lots of subject knowledge at once. They demonstrate their comprehension of the speech itself, bringing its key themes and ideas to their poem. But they’re also showing knowledge of the conventions of poetry, particularly in creating a poem that sounds pleasing and rhythmic when read to an audience. Through writing poetry, spending time working on cadence, repetition, sound and figurative language, students are deepening their understanding of what makes great rhetoric.

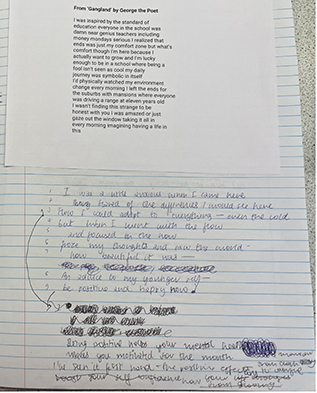

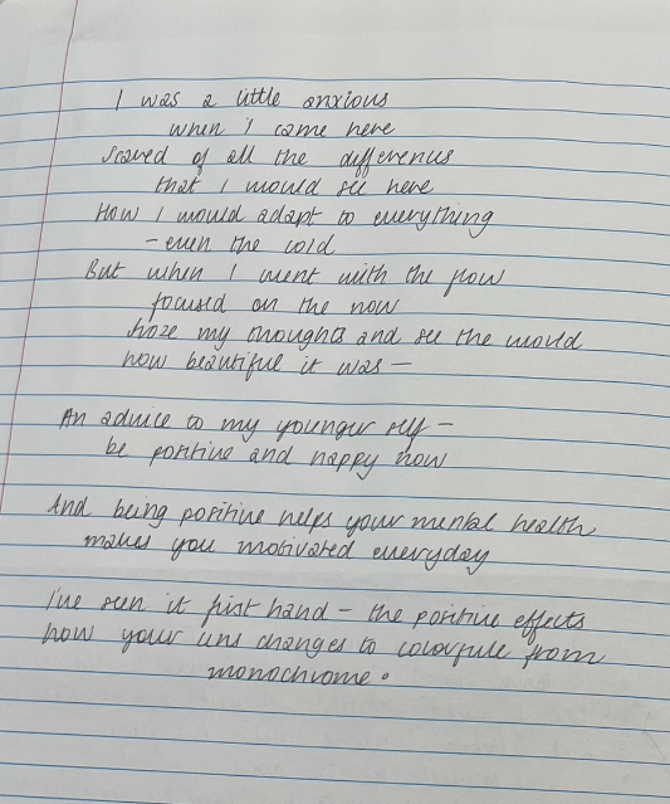

In another example, a student is using George the Poet’s ‘Gangland’ as inspiration for their own poem. The original is a spoken word, free verse poem about the poet’s experience of growing up on an estate in Neasden, Northwest London, while attending a selective grammar school in Barnet. In their own poem, the student is able to show their comprehension of the poet’s alienating experience through their own experience of moving to a different country. They also capture a sense of the original poem’s tone and language. What’s interesting in the student’s work is that they initially stay close to the ‘Gangland’ model, but in their redrafting and additions to their draft, they extend past this to offer advice to their younger self.

Assessing, evaluating and writing back to famous speeches

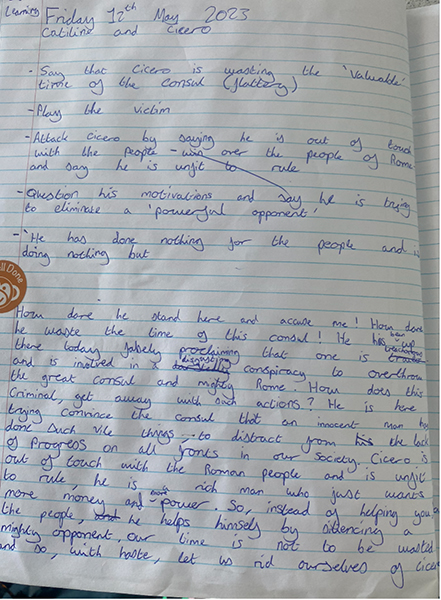

In reading and responding in writing to famous examples of rhetoric in literature, these students are able to experiment with style and try out different voices in their own speeches. These examples demonstrate the value of this: through imitation they are able to convey emotion and passion by using language in the style of the characters. This shows the teacher both the students’ grasp of the original speech and the character and style of Catiline, but also how great rhetoric can be created – we see them using repetition and punctuation creatively. In one of the pieces, the student has written a list of reminders like ‘attack Cicero’ and ‘say Cicero is wasting time’ which they bring to life in the speech that follows.

Extended draft speeches and shorter experimental bursts on a variety of topics

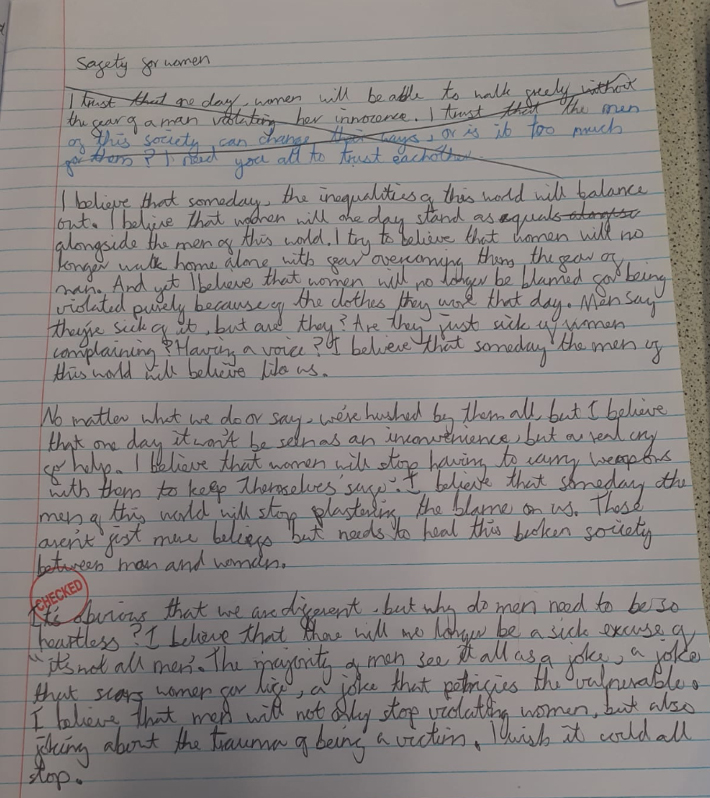

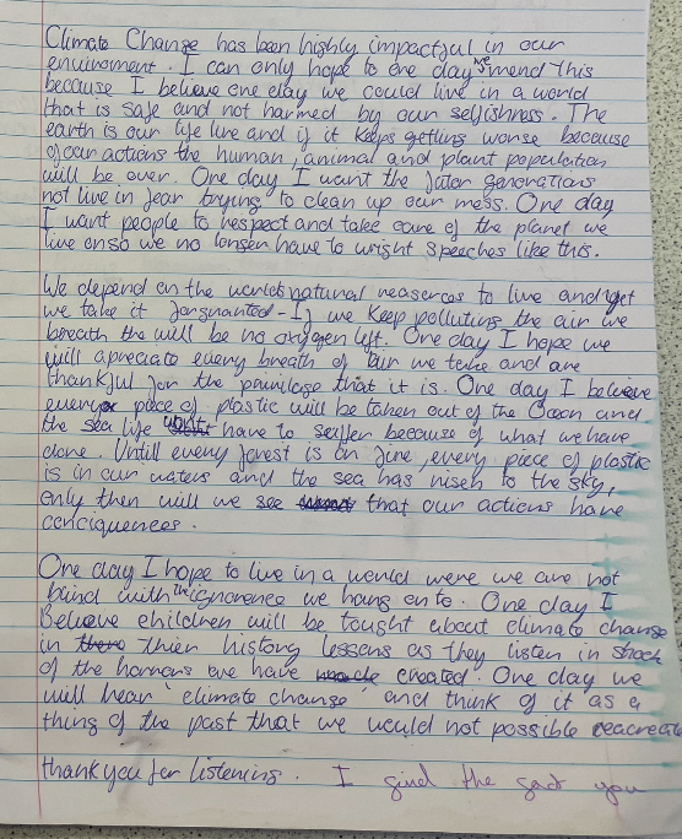

In these pieces, the Year 9 students were writing about topics of their choice, which gives their writing a confident, informed tone on a range of heavy-duty topics: climate change, poverty, violence against women and inequality. Being given the freedom to choose the subject matter seems to have enabled students to invest thought, time and effort in their work, reflected in their substantial length and the quality and detail of their ideas. The students are using convincing, mature and emotive language to engage with their audiences – for example, in the climate change speech, the student imagines an alternative future in which children will be taught about climate change in their history lessons ‘and listen in shock at the horrors we have created’. In the speech about violence against women, the student creates a sophisticated contrast between the darkness of a world of violence and the light of a world without it by developing and sustaining an extended metaphor: violence is ‘a dark cloud that hangs over the world, casting shadows on everything it touches’, and in opposition to this, the audience are positioned optimistically as the ‘light that breaks through the cloud’. We can also see the influence of the speeches they’d studied in the rhetoric unit on their own writing: ‘I have a Dream’ echoes in the speeches about climate change and inequality in repeated phrases like ‘I believe that one day’, the dramatic contrast between current and future worlds, and the emphatic use of ‘will’ to confidently assert the vision of future world in which the wrongs of today have been eliminated. Students have absorbed King’s style, tone and methods and made them their own.

Students did more writing

Students at both schools were generating lots of writing. Once the curriculum had been adapted, students had more time to develop their writing in lessons in lots of different ways, rather than have every piece of writing directed towards the final assessed piece. At John Stone Community School, students across all attainment levels got more writing done than they had previously. Chloe, the KS3 Coordinator, commented:

I’ve seen in my books and a lot of the other books within the department more writing, more work being generated by the students, and more extended pieces of writing because it’s more of an attitude where it’s exploratory like “I’m going to try and write in second person today because I’ve seen it in the example and I thought it was pretty good I’m going to try and do it, it might not work. We’ll have a look and see what happens.” And I really celebrate that, that’s really good.

When visiting the school, we saw lots of evidence of what Chloe had to say. In one particularly striking example (see attached PDF2), we get a really strong sense of the student and their knowledge and skills in English. We see them doing many of the activities we might expect in a short stories unit: they are summarising their understanding, engaging with themes and ideas, asking questions of the stories and making predictions about them before reading. But what’s most interesting about this unit of work from the project is how often students are able to write their own stories based on those they have read. This is in stark contrast with the work we saw from John Stone in blog 2, where the only significant pieces of writing were ‘the formative assessment’ and ‘the summative assessment’, which were asking students to demonstrate very limited knowledge and skill in a particular written form. Instead, here, we have so much material to formatively and, if we want to, summatively assess - the student is demonstrating an enormous amount of subject knowledge across a range of areas. In their recreation of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s challenging story, ‘Tomorrow is Too Far’, for example, we see them working really hard to create the unsettling, candid second person narrative voice of the original story, as well as the unusual structure – not at all a straightforward task! They move adeptly and with enthusiasm between genres and there's so much engagement with the stories evident. In their plan for a recreation of Jessie Greengrass’s story ‘The Decline of the Greak Auk’, we see how they use the concept of extinction, applying it to a different setting and context. They plan to bring Greengrass’s original message to their story in their own way – that if we can do this to innocent creatures, there’s no telling what else we might be capable of. The work is impressive in its scope, and demonstrates what a year 8 student can do when they are offered some creative choice, interesting material and time for writing.

Greater variation in student outcomes

We’ve already outlined the problems with the dominant assessment model, a key one being that it limits variation in student responses. Because students are tightly guided in what to write and how to write it, working to a narrow set of attainment outcomes, students in any given class often produce very similar pieces of work. This risks giving the illusion of success and presents problems for formative assessment. How can you identify how well a student can write if the writing is not authentically their own? You can only really assess how well they can absorb and reproduce directions to write in a particular way.

There was a spread of attainment levels in the written work completed by students during the project, in keeping with what you would expect from their prior levels of attainment. Teachers were able to tell where genuine progress was happening and also identify in what ways different students would need to develop their writing. This was further helped by the fact that students were producing more written work in a variety of forms, so giving teachers more material to work with, and also providing students with more to peer assess and to reflect on themselves.

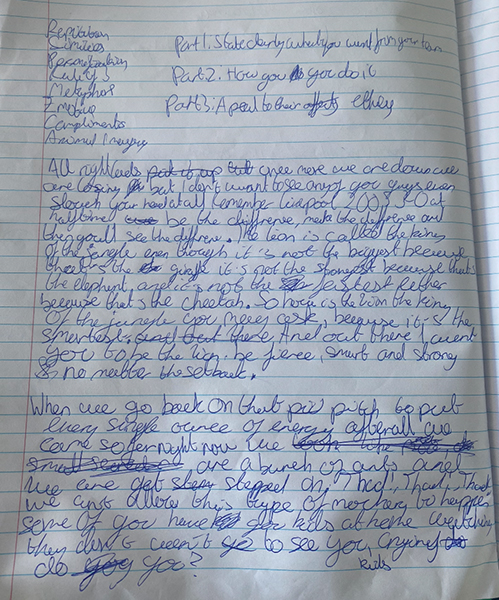

In many instances, students who had been reluctant to write before the project began reacted positively to the flexibility and creative possibilities offered by the new approach and demonstrated improved engagement in their writing. In this example, one teacher at Kiteford noted how much more a middle-attaining boy had written than he usually would, when offered the chance to write a piece designed to motivate his football team. In this work, he shows he’s thinking about the writing being read aloud – he's capable of creating a lively voice, with clear aspects of genre and evident effort in terms of selecting vocabulary and metaphors to suit the piece. Had he not been offered this opportunity and an element of choice, his teacher said, he would have produced a far less interesting piece and she, in turn, would not have had this raw material to work with formatively.

In summary

An increase in the volume and variety of writing seen in both schools after their curriculum adaptations surprised the project teachers in pleasing ways. With students getting more work done, teachers had a much clearer understanding of what students could do and what they needed to do next. It meant they could plan responsively and adapt their subsequent lessons intuitively. It helped them build their understanding of how well each student could write for different audiences and purposes and it turned their classrooms into places where learning came through the ongoing exchange of ideas between teacher and student.

These changes to their classrooms meant they were able to explore some of the other research questions. In our next blog, we’ll take a look at one area of formative assessment that emerged as a natural consequence of all this writing: teacher feedback. Check back soon!

*All school and teacher names in this blog have been anonymised.