One

Earlier this month I received an email from an A Level student pitching an idea for an article for emagazine. I get a lot of these emails and usually say, ‘go ahead and send it to me’. This one sounded promising:

I wonder if you would be interested in an article on Hamlet, possibly titled ‘Suicide in Hamlet’s First Soliloquy’. My aim would be to write an engaging short article exploring Hamlet’s soliloquy in Act 1, Scene 2, focusing on how language is used to convey the theme of suicide, Hamlet’s motivations, and his inhibitions.

It looked interesting but I wasn’t going to get my hopes up too quickly. Sadly, in recent years, it has often been rather disappointing to see what students mean when they talk about ‘focusing on how language is used’ to convey a theme, or develop a character. The pieces sent in, though clearly showing the energy and commitment of high-attaining and enthusiastic students, often adopt approaches that are much less productive than they might be. It is not uncommon to see a lot of word-level exploration that isn’t connected to meaning, or is used to make points that are flimsy at best, implausible at worst. Students also seem to have got the idea that the more literary terms they use the better, regardless of whether they help the argument or not. (Those who know my work, will be aware that this is something I have been flagging up as a concern for a very long time.) Students also often compartmentalise – ‘I’ve said something about language [usually only word-level comment], and now I must say something about structure.’ And they tend to think in terms of paragraphs – a paragraph on this, followed by a paragraph on that – rather than in chains of ideas, or flows of thought. Each paragraph is created in isolation and does not build up a sustained argument. Perhaps this is the result of the focus on the individual paragraph at GCSE, rather than seeing paragraphs as leading into one another, as part of a sequence of ideas, developing a whole, coherent reading of a text. (The word coherent means just that, that the constituent pieces hold together.)

OK, so Abi’s piece arrived in my inbox. And what a piece it was! Here’s a little extract, to give you a flavour of it. The full piece is in emagazine.

Perhaps the most convincing explanation for Hamlet’s despair is his loss of faith in humanity and the world around him. The Edenic ideal of the world as a ‘garden’ looked after by the human race ‘grows to seed’ as humanity fails in its task as gardeners, and the world remains ‘unweeded’. The lack of distinction between good plants and weeds, such as Hamlet’s father and Claudius, (with implied blame on Gertrude for her lack of judgement) has led to a world ‘Possess[ed]’ by ‘rank’ and sinful leaders. Hamlet’s certainty that the world is corrupted by unpunished evil foreshadows the Ghost’s revelation of murder in Act 1 Scene 5.

In this paragraph, one can see how assured Abi’s writing is, and the way in which comment on language and the detail of the text is integral to her arguments and her discussion of meaning. This, for me, is what language discussion should be all about. She doesn’t feel the need to unpack the meanings of individual words for their own sake but rather in the service of interesting ideas.

Having said that, there were a few places where her argument did not seem so convincing and it was what happened next that lifted my spirits even further. In the paragraph that followed, she seemed to be arguing for a rather complex set of ideas about time in Hamlet’s soliloquy, which ignored some of the more obvious, but very important, human emotions at stake.

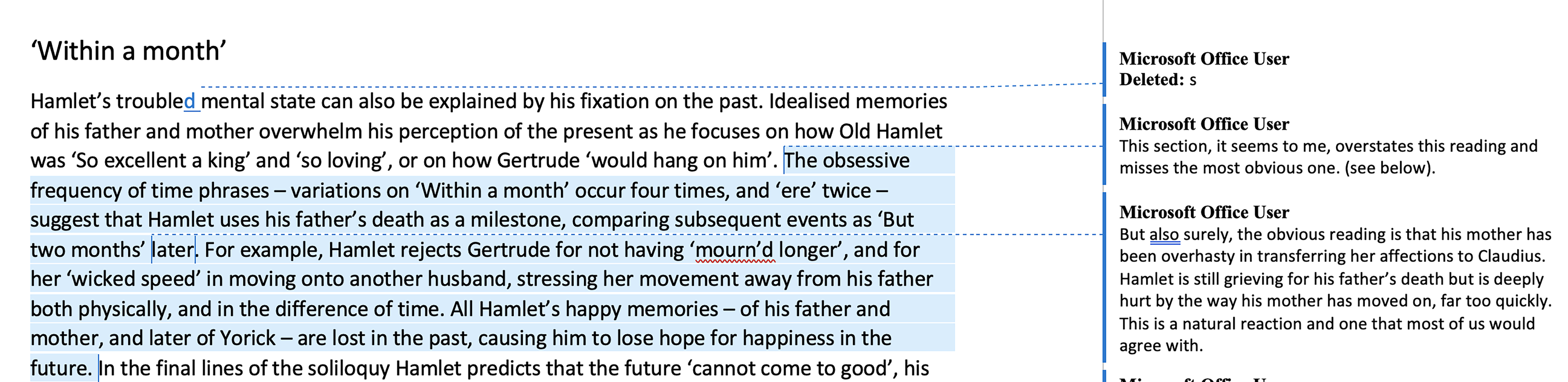

Hamlet’s troubled mental state can also be explained by his fixation on the past. Idealised memories of his father and mother overwhelm his perception of the present as he focuses on how Old Hamlet was ‘So excellent a king’ and ‘so loving’, or on how Gertrude ‘would hang on him’. The obsessive frequency of time phrases – variations on ‘Within a month’ occur four times, and ‘ere’ twice – suggest that Hamlet uses his father’s death as a milestone, comparing subsequent events as ‘But two months’ later. For example, Hamlet rejects Gertrude for not having ‘mourn’d longer’, and for her ‘wicked speed’ in moving onto another husband, stressing her movement away from his father both physically, and in the difference of time. All Hamlet’s happy memories – of his father and mother, and later of Yorick – are lost in the past, causing him to lose hope for happiness in the future. In the final lines of the soliloquy Hamlet predicts that the future ‘cannot come to good’, his prophecy foreshadowing the spying, murder, madness, and suicide that seemingly prove him right.

However, Hamlet’s grasp of time and memory is uncertain – he says that his father is ‘But two months dead’ and then corrects himself – ‘nay, not so much, not two’. His memories of his father are too perfect to be true, and his fixation and anger at his mother’s betrayal borders on obsessive.

I wrote back to her with a version that raised some questions compiled by me and co-editor, Lucy Webster. Here’s what I said:

In this case, as in a few others, what came back from Abi in the next version had fully taken on board the comments and re-worked the thinking in a very productive way. It wasn’t just adding, it was reflecting and re-thinking. Here’s the revised section:

Her writing – excellent at the outset – but offering an argument that wasn’t wholly convincing, was immeasurably improved by this kind of critical interaction and she rose impressively to the challenge of being pushed to think again.

This experience is a heartening one, but it also raises some important ideas about what we should be doing with students. The exchanges between me and her were not about fulfilling exam criteria, nor were they about proof of ‘academic’ writing or indeed ‘proof’ of any kind. They were about the text itself and her ideas about it. They were about the substance of literary discussion of a text, not the form. For me, this has implications for the way we look at writing more generally in literary study. Whatever Abi’s teachers have been doing, they have done a brilliant job in getting her to think hard about Hamlet, how it is written and the kinds of arguments that make studying it so fascinating. Equally, they have encouraged an approach to essay writing, and to critical comment, that is very impressive.

Two

Another reason to be cheerful about student writing.

A week or so after accepting Abi’s article for publication in emagazine, I received another email, this time from a teacher, about something that six of her Year 13 students had done, working collaboratively in a lesson at the end of term, just to have a bit of fun. She was excited by what had emerged. It was a poem, written with Julia Donaldson’s Gruffalo as its inspiration, and based on their study of Angela Carter’s 'The Bloody Chamber'. Now this might sound a little strange, but when you think about it, Carter was renowned for her reworking of fairy tales and folk stories and her magpie-like intertextual borrowings and re-workings.

I read the poem and was astonished. What the students had done was quite extraordinary. I often talk about creative-criticality, how creative responses can provide critical illumination on texts, and I’ve included the writing of a poem based on a prose text as an activity in several EMC publications. But this A Level example was beyond the realms of what I might have imagined possible. When I then asked them to write a commentary about their choices and the relationship to ‘The Bloody Chamber’, it took them just one day to come back with a superb commentary, explaining how the poem reflected Carter’s concerns, preoccupations and style.

Here is the opening of the poem.

These Gothic Pages

A girl took a stroll in a deep dark wood

A Marquis saw the girl and the girl looked good.

“Little girl, are you in danger?

Come and explore my bloody chamber.”

“It’s terribly kind of you, sir but no,

I’m going to the countess’ chateau.”

“Which countess do you mean?”

“The countess, you know, the vampire queen.

She has a whore’s mouth and pale, pale skin

And she doesn’t let any light in.”

And here is one part of the commentary:

We chose The Gruffalo by Julia Donaldson and thought that retelling The Bloody Chamber by Angela Carter would work particularly well given the fairytale form that Carter both adopts and subverts. We found it interesting that the original Gruffalo is quite gothic in itself presenting us with an opportunity to subvert the “latent content” just like Carter does.

Our female protagonist is a blending of all Carter’s women in the collection, inspired by a critical interpretation by Kathleen Manley of the text that describes them as ‘women in process’. Firstly, she is left unnamed in a typical Carter-esque manner. Secondly, she is strolling through woods, like the girl in ‘The Erl King’ or the girl in ‘The Company of Wolves’. Most importantly, she feels no fear and successfully manipulates and scares off the threatening Gothic male figures who invade her path and seek to harm her.

Final Thoughts

Both of these experiences, seeing A Level students doing wonderful writing on texts, raise important issues about how we work on texts with students – how we respond to their writing, whether we allow them to ‘have a bit of fun’ sometimes to see what emerges and the value of collaborative work.

But one other question that has emerged for me is wondering why it is at this very moment that we’re seeing such great writing. It isn’t just these two – the quality of writing submitted to us for publication recently has been better than it’s been in an awful long time. I don’t have any clear answers but one that is definitely worth considering is whether it has anything to do with Covid, the lockdown and the absence of final exams. Is it that students are being given more open tasks that are not narrowed to exam requirements, such as the poem activity? (Even the soliloquy piece doesn’t follow a typical ‘exam essay’ pattern). Is it that students are being given more space to breathe, to think their own thoughts and pursue ideas independently? Is it that the general climate is shifting, with a greater recognition that there is more to good writing at A Level than ticking boxes and being ‘trained’ to follow a formula?

It would be good to find out. It’s imperative that we do find out, in fact, in order to build on this, rather than lapse back into the more stale and formulaic writing that’s been more common in recent years. If you’ve noticed a change yourself, with your own students, in your own practices and in your own classroom, please shout about it. Please tell us why.

Thank you to the student in the first example, who kindly gave permission for me to publicly share her drafts as well as extracts from the final article. Thanks too to the students who wrote the poem and commentary, and their teachers, for letting me share extracts in this blog.