Our previous blogs have mostly focused on these research questions:

- What is the relationship between formative and summative assessment in English?

- How does formative assessment work best in English classrooms?

- What happens when students spend more time reading, writing and editing their work in English?

- What happens when English teachers have time to read and respond to student work?

- Are there barriers to using formative assessment effectively in the English classroom?

- What happens when a single piece of assessment is removed from the end of a unit of work?

The questions we are yet to turn to, and which this blog will attempt to address, are more focused on what happens when we want to summarise or reflect on student attainment, either as part of our ongoing classroom practice or for reporting purposes:

- What happens when English teachers moderate and standardise KS3 work together regularly?

- What happens when a range of student work is used to summarise student attainment in English?

If you’ve read any of our other blogs, you can probably tell that we are passionate about the importance of meaningful, frequent formative assessment. Of course, we also know that summative assessment is a fundamental part of life in schools. We hope we’ve made it clear by this point in the series that end of unit summative assessment pieces can dominate curriculum planning and genuine formative practices, but that doesn’t mean that we think summative assessment is bad or unnecessary full stop – far from it. There are clearly times when teachers need to summarise their students’ achievements and to find ways to meaningfully record and communicate these to senior leadership teams, parents and students.

Something we wanted to explore in our research was how the more developed, wide-ranging writing generated in student books during the revised project units of work could be used to assess students’ progress.

How did the project schools manage the process?

The Research and Projects team asked both project departments to meet at least once during the teaching of the unit and once at the end, to compare and discuss the student work. We hypothesised that if departments could make time for this and make it an ongoing process, teachers would have higher expectations of their own students’ work going forward, having gained a sense of the quality of work across different classes. We hoped that as a result, expected standards would go up and teachers would see and expect better quality work from students.

However, both departments understandably found it difficult to make time for the mid-unit meeting alongside the demands of KS4 and KS5 moderation. This is a problem endemic to our current linear exam-led secondary education. When we talk to English teachers about this, they know that they should be spending more time thinking about standards at KS3, understanding that there would be far less need for intervention at KS4 if they were able to do so, but they simply cannot fit it in.

At John Stone Community School, the Research & Projects team joined the English department for an end of unit meeting, which they used to summatively discuss and assess the work done by students during their short stories unit so they could report data to parents. As we detailed in blog 3, this unit took a new approach to curriculum and assessment – the end of unit dominant assessment model was removed, and work completed no longer built up to an end of unit formally assessed piece. Students did lots of varied writing across the unit.

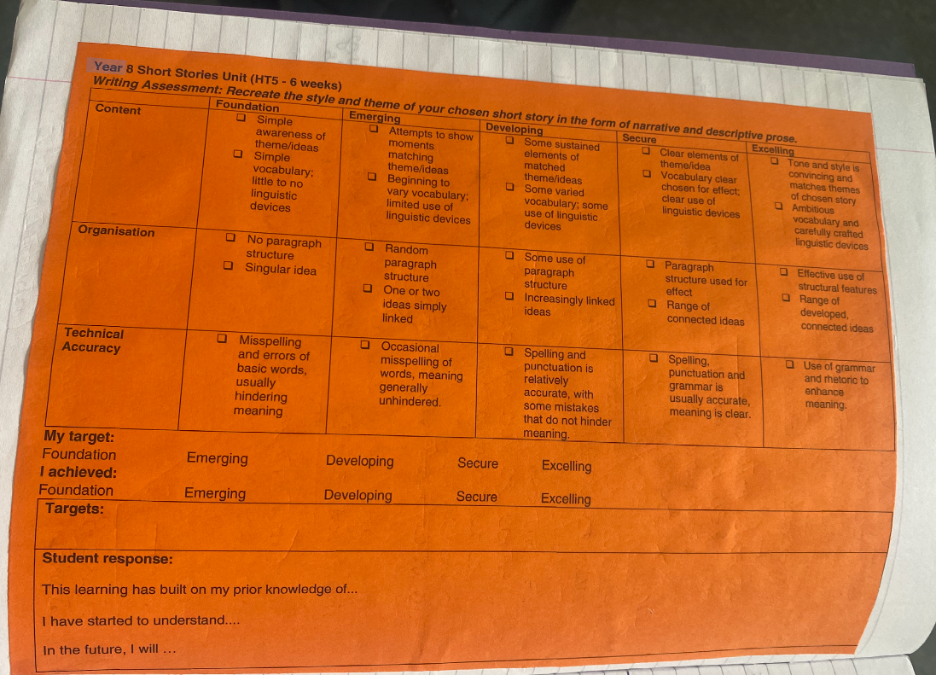

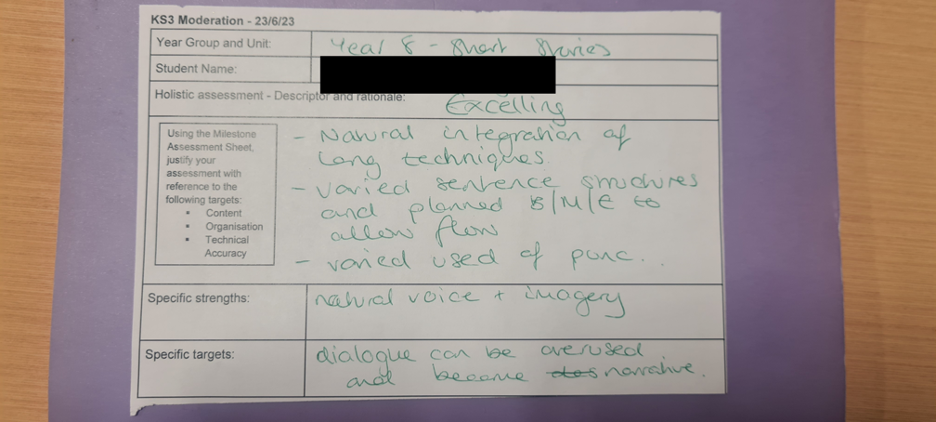

In the meeting, led by their KS3 Coordinator, teachers sat in small groups with piles of their exercise books and completed moderation slips based on the work in students’ books and the descriptors on their ‘Milestone Assessment Sheet’ (MAS) for the unit. These sheets followed a format used in every subject across the school for end of unit assessments, with the reporting terms ‘Foundation’, ‘Emerging’, ‘Developing’, ‘Secure’ and ‘Excelling’. Teachers kept their moderation slip notes to themselves until a subsequent discussion with colleagues, in which they shared and talked through individual students’ progress, reminded themselves of breakthrough moments, compared pieces of writing within books and between students, raised important points about the challenges of not ascribing summative descriptors to one ‘final piece’, but the range of work in an exercise book, and adjusted their assessment accordingly.

Below is an example of the MAS from the project unit on short stories. You will see that despite the change to the way this unit was designed and assessed, the focus and descriptors are very much borrowed from GCSE Language paper writing task descriptors.

Here's an example of one of the moderation slips completed by a teacher during her assessment of a student book.

The department continued using the MAS for practical reasons during the project, and it was helpful in allowing them to reflect on its fitness for purpose, and what needed to change. They were able think afresh about what each reporting term meant in relation to the very different student work generated during the project unit, and whether their criteria were valid. By the time teachers came to summatively assess the work of the unit, they realised there were several issues with the MAS and what they were looking for in student books to summatively assess. They found:

- The focus on writing alone was limiting: what students were doing during this unit (see blog 3) demonstrated much more than the writing skills accounted for on the sheet. In fact, the teachers reflected on how much students’ creative writing showed them about students’ comprehension of the stories. They were able to learn lots about students’ reading ability through the work of the unit. Since the project, the department have been working to address this, aiming to ensure coverage of reading, writing and speaking and listening in each unit.

- The criteria for achieving each band were problematic: the focus is primarily on small, technical aspects of the writing (‘local operations’), with only a single, vague comment – ‘natural voice and imagery’ – addressing the more important bigger picture elements (‘global moves’) that make up successful creative writing. There’s perhaps a problem with the wording of the MAS itself (and so with the wording of the GCSE assessment objectives it draws on). The content criteria in large part are not about ‘big picture’ content at all, but about the small stuff - vocabulary and linguistic devices. Absent are references to aspects of writing that would align assessment with the writing tasks undertaken, such as to characterisation, the development of ideas, the use of setting, matching the content to the audience, and so on. Tone and style are mentioned in the ‘Excelling’ but nowhere else. Does that mean that lower attaining students are not expected to engage with these concepts?

- This KS3 mark scheme – like many we saw in schools - was taken from the lower end of a GCSE mark scheme. This means that even middle-attaining students, according to these criteria, might have a ‘random paragraph structure’ and only the work at the top end is expected to convincingly match the tone and style of the chosen story – something that should be happening in the majority of the stories, given that students were writing re-creations. The criteria don’t seem broad or ambitious enough.

- The process was difficult without exemplification. In a subject like English where we often assess developed pieces of writing, collecting exemplar work to act as indicative content is crucial. It is very difficult to understand level labels and descriptors in the abstract. The department decided that, for each unit and over the years, they would collate examples of work from books at each level to set an expected standard.

These points highlight the importance of properly getting together, as a department, to unpick ingrained, long-accepted practice. Large scale change is incredibly difficult and time-consuming to achieve in schools, but John Stone’s department are now reviewing each of their units and assessments. They are still required by the school to use the MAS, but they are ensuring that they moderate and exemplify student work and that their focus and descriptors properly match the learning that takes place in each new unit.

Teacher reflections during the discussion

Below are a range of interesting teacher comments from our recording of the meeting at John Stone. These reflections get to the heart of many of the issues we encountered in our discussions with schools during the project.

Greg reflected on how students have come to understand assessment and feedback, as a result of the dominant assessment model the department previously used:

‘You … get students who are just great at writing but... they just can’t be bothered to write if they don’t think that’s the thing that actually matters... There’s a student in our class that we had before and he used to constantly be like... “is this the assessment?”... “does this count?”... And I’d be like ‘everything counts’ but... then I didn’t have a leg to stand on because he was kinda right. Everything he was doing was a build up to the one thing his parents are looking at.’

‘And the thing is we are always giving them feedback... it might not always be written. The kids need to know that they’re constantly... it’s not about a piece of paper or a grade. It could be something they’ve shared, it could be something you or another student has commented on. So I think feedback, it should be something more visible. It shouldn’t just be end of term, here’s your grade. They should know it happens all the time. It’s formative assessment.’

Chloe thought more about the school’s reporting terms and what they mean for student progress:

‘My experience of it, whether by design or by mistake, is that it produces a bit of a bell curve… [The ‘developing’ descriptor] feels so much wider and heavier than all the other bands. I find so many pupils fall into this ‘developing’ band. I find it very easy to get them up to [‘foundation’ and ‘developing’] ... but this then seems to cover a massive range of pupils and then I find it very difficult to break into ‘secure’ and ‘extending’.’

Greg raised the issue of only using written work to assess a students’ understanding in English:

‘This is [student name]... This is someone with very good ideas who’s just not getting them down on to paper, and not getting them down on to paper quickly enough. And they’re really tricky because what do you give them... I can’t mark those thoughts, I have to mark what goes down on the paper... Verbally he’s very strong.’

Making it work beyond the project

It is a challenge to shift away from the dominant assessment model and towards this less crisply defined, more holistic way of assessing students – not least because even ringfencing some time to meet and moderate for KS3 is difficult. But it is, we think, closer to what Bethan Marshall describes as the 'horizons, not goals'[1] nature of the subject, in which progression is not easily defined, and for which a blend of the work of the course and exams have historically been considered most appropriate.

Initiating a moderation process like John Stone’s raises lots of questions which are important to think through carefully as a department. The more departments are able to repeat the process and revisit the questions below, e more likely the process is to work in the long term; it relies on individual teachers sharing an understanding about how to judge student work. As teachers develop through this process, this should feed into their planning and teaching.

Questions to consider with your teams:

- Which different types of writing do we want to see from students, and why?

- How much weight should be given to each piece of work?

- How long should a piece of student writing be to be able to draw conclusions from it for assessment?

- In what conditions should pieces of work be written?

- How many pieces of writing are enough to build up a rounded impression of student attainment?

- What can self and peer assessment add to our understanding of student progress?

- How much time do we need to spend on making a judgement about each student?

- What role should students’ verbal contributions across a unit/term play in this kind of summative assessment?

- How do we avoid bias in our judgements?

- Which criteria do we want/have to use for our judgements? What are the pros and cons of these?

- How should summative assessment outcomes be shared with students, parents and SLT?

Moderating student work: benefits and challenges

Perhaps most crucially, the time spent moderating needs to move a department’s teachers closer together in terms of the way they value work at different levels. Achieving a shared understanding across a large team is not easy, which is why the time spent reviewing work together is such a crucial part of the process. Regardless of whether any resulting data is used for reporting, it’s also vital for creating a shared departmental vision and ethos, as well as training less experienced staff, who will have seen less student work than more experienced colleagues. We also think that summatively assessing like this puts trust in teachers’ professional judgement and expertise in a way that other systems do not – and we are, of course, all for putting trust back into English teachers’ knowledge and professionalism!

We’d also argue that making judgements about students’ work becomes easier once the focus has been shifted so that teachers are constantly immersed in the content of their students’ books: reviewing work during and after lessons, live marking, narrating the best bits of writing during the process, and reviewing samples of writing to feed forward into next lessons, for example. In other words, if these good formative practices are embedded properly in classroom pedagogy, teachers are honing their ideas about what makes great English work every lesson, and moderation sessions should become a more intuitive process over time.

Our top five tips for making it work in your department

- Take your time! You might need to fight to get department time for moderation, and you need to be patient as you take the time necessary to embed the approach – regularly revisiting your standards, being open to debate and discussion and disagreement, and being realistic about timelines. This is a process that will never be finished, and might take a long time to get up and running!

- Build up a bank of student work Keep whole exercise books at the end of each year, exemplify different levels of attainment, scan in annotated copies of student writing from each unit as you go. The first year, this will take some time – the second year, you’ll be very grateful you bothered!

- Review your curriculum regularly Re-evaluate your units of work and ensure they’re generating the right range of student writing to help you make valid judgements.

- Get students to buy in Tell students you are shifting your focus for assessment from the summative end product to the formative, ongoing work of the unit, and explain why this is better for their progress in English. Show them your thinking, and encourage them to reflect on their work. This way of thinking about English is more inclusive: no student, however good they are at English, will ever master it fully; all students, however good they are at English, can make progress in this model because the processes of experimenting with, reflecting on and redrafting their own ideas are at the heart of it.

- Show your working to parents and SLT English is special and different, and assessment in our subject needs to recognise and value this difference. We know this, but it can be hard to explain to people from outside the discipline. Take time to hone your rationale and practice explaining it to colleagues working in different subjects.

But what about exams?

This way of doing assessment priortises teacher expertise, formative practice and student learning in the classroom over exam preparation and testing, but it doesn’t exclude the possibility of exams and tests in timed conditions. As we’ve mentioned before, the word ‘assessment’ in schools is often used to refer to a single piece of work, and seems to have replaced the words ‘exam’ or ‘test’. Reintroducing the idea of assessment to students as something formative and ongoing, as we have shown, can have a positive effect on the work they produce from lesson to lesson. Greg shared his thoughts about reframing the word ‘assessment’ with his class during the project:

‘I’m looking at you and what you have produced as a writer, as someone who comprehends literature. What do you know? What can you do? That’s what I want to know. And they calmed down a bit after that. But it’s that word assessment. Even we use it in a skewed way and they pick up on that. And then everything is the be all and end all of assessment and suddenly it’s a big scary thing and actually when you break it down, assessment is just what are we doing and how can we move forward.’

Our thoughts are that giving students an unseen test or exam at the end of the year would be useful and interesting as a formative, feeding-forward process, too. In John Stone’s case, an aspect of such an end of year exam might be reading and writing based on a short story students haven’t seen before. This would test students’ retention of knowledge and skills learnt as part of the short stories unit. Whether or not schools chose to report this data in some way would, of course, be an individual and contextual matter.

Looking beyond the project

The English team at John Stone continue to work on their assessment model, and have fully invested in what they are calling ‘holistic judgement’, using a range of student book work as the basis of their summative assessment. It's been really gratifying to see the team run with the project and make it their own, extending its reach across their KS3 cohort.

Since running the project with our two schools, we’ve also shared our findings with teachers from a network of other schools across the country in our Rethinking Formative Assessment Working Party. These teachers are currently using some of their own students as ‘case studies’ as they put the focus back onto their formative practice and consider the impact it has on students’ learning across a half term, taking the spirit of the project forward in new contexts. We are looking forward to our next meeting in the summer term, when they’ll be sharing what they’ve found.

We’re continuing to update our blog in installments - next, we're hoping to publish a conversation between our colleagues from John Stone about their ongoing assessment work and some reflections from the teachers in our working party.

And finally, to wrap up the project, we will be hosting an Assessment Conference at the EMC’s Webber Street home on 28th June this year. We have an exciting line up, featuring a keynote from Kings College’s Bethan Marshall, workshops with teachers from both of our project schools about the practicalities of improving assessment at KS3, a live moderation session by EMC’s Barbara Bleiman and a discussion about assessment with a panel of education experts, chaired by EMC’s director, Andrew McCallum.

[1] Marshall, Bethan, ‘Goals or horizons—the conundrum of progression in English: or a possible way of understanding formative assessment in English’, The Curriculum Journal Volume 15, 2004 - Issue 2, Pages 101-113. Published online: 04 Jun 2010. [Accessed at: https://doi.org/10.1080/0958517042000226784]